denkste: puppe / just a bit of: doll | Bd.3 Nr.1.1 (2020) | Rubrik: Fokus

Holy Puppets: The Double Nature of the Medieval Bust Reliquary1

Michelle Oing

Focus: Puppen/dolls like mensch – Puppen als künstliche Menschen

Focus: Dolls/puppets like mensch – dolls/puppets as artificial beings

Abstract:

The essence of puppet performance is its balance between animacy and

inanimacy,

the artificial and the natural. This article proposes the framework

of puppetry as a means of understanding the transcendent potential of a group

of medieval reliquary busts from Cologne. In both appearance and manipulation, these

sculpted busts blurred the boundaries between life and death, much like puppets. I argue

that the dual mimesis of these busts, both visual and kinetic, enhanced their theological

purpose as vessels for the bones of saints, and points to a medieval interest in the productive

paradoxes of representation. Through their puppet-like hybridity, these sculptures

bridged the distance between humans and the divine for medieval viewers. The article

concludes by proposing a parallel between the temporary lives of puppets and the hybrid

nature of artificial intelligence, suggesting that medieval conceptions of mimesis can

provide

a means of thinking through twenty-first century technology.

Schlagworte: relics; reliquaries; sculpture; mimesis; hybridity; theology; medieval studies; puppetry; animation

Zitationsvorschlag: Oing, M. Heilige Puppen: Die Doppelnatur Des Mittelalterlichen Büstenreliquiars. de:do 2020, 3, 28-37. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/5594

Copyright: Michelle Oing. Dieser Artikel ist lizensiert unter den Bedingungen der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International.(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de).

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/5594

Veröffentlicht am: 20.10.2020

Um auf Zusatzmaterial zuzugreifen, besuchen Sie bitte die Artikelseite.

The puppet’s hybridity

While the puppet is decidedly not alive, it is not exactly dead, either.

When used in performance, the puppet occupies a liminal space in

which the boundary between the animate and the inanimate is destabilized.

Each gesture the puppet performs evokes an entire network of dualisms,

only to suggest that they are not as separate as one might hope: the puppet is both

animate and inanimate, real and copy, artificial and natural.

In its assertion of both/and, or neither/nor, the puppet proclaims its hybridity.

Like all hybrid beings, it is an ambivalent creation, inspiring both fear and desire.

We can see this fear of the hybrid in Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio (1883), where one

of the first acts of the newly animated puppet is to disrespect its maker: “Before

the mouth was even finished, it began to laugh and mock him” (Collodi 1883, 9).

However, the other side of this ambivalence is important, too – a desire for the

potential that arises from the puppet’s hybridity.

Both scholars and puppeteers have long recognized the productive potential

embodied by the puppet’s simultaneous animacy and inanimacy. The concept

of “double vision,” as put forth by Steve Tillis,

offers the best means of understanding this ontological

tension. Tillis uses this phrase to refer

to the audience’s experience of the puppet, in

which they see it, at one and the same time,

as both “perceived object” and “imagined life”

(Tillis 1992, 7). As a result of this dual nature,

the puppet “pleasurably challenges its audience

to consider fundamental questions of what

it means to be an object and what it means to

have life” (ibid., 7).

Figure 1: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1330/40.

It is in this “pleasurable

challenge” that the power of puppetry lies, in

its ability to push the audience to reflect on

their own conceptions of the animate and the

inanimate, the real and the artificial.

As John Bell writes, despite the frequent marginalization

of puppetry, this medium “is always

a serious matter, a play with transcendence,

a play with the basic forces of life and death” (Bell 1996, 19).2 In what follows, I will explore the powerful, transcendent play of

a group of objects which, too, were seriously engaged with meditations on life

and death: the medieval reliquary busts of the companions of Saint Ursula from

Cologne (cf. figure 1-3).

Like the puppet, these sculpted busts combined an anthropomorphic appearance

with the ability to move, lending them an “imagined life.” At the same

time, however, they asserted their objecthood in multiple ways, creating the double

nature

– or “double vision,” in Tillis’ formulation – that is the essence of the puppet.

To suggest that the Ursula busts were analogous to puppets is not simply

to give them a new name. Puppetry supplies a new interpretive framework for

exploring how these artificial avatars of the sacred were encountered and understood

in medieval Cologne. The question at the heart of this article is how the

visual and kinetic mimesis of these busts enhanced their theological purpose as

vessels for the sacred bones of saints. Seen as puppet analogues, the dual mimesis

of these busts points to a medieval interest in the powerful, productive paradoxes

of representation, and their utility as devotional tools to span, at least temporarily,

the distance between humans and the divine.

The first section introduces the reliquary busts of Cologne, and suggests the

ways in which the lens of puppetry can clarify their use. In the next section, the

busts are presented as objects in action, combining the simultaneous suggestion

and denial of life to inspire “double vision” in those who view them. Finally, Iconclude

by exploring how the double nature of these busts amplified their theological

aim, calling attention to the holy relics contained within.

Figure 2: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1350

The Ursula busts of Cologne

The so-called Ursula busts were mass-produced in Cologne beginning in the

twelfth century, with the majority produced between 1270 and 1360, in order to

house the bodily relics of St. Ursula and her eleven thousand companions (Urbanek

2010, 37).3 They thus form an important material component of the medieval

cult of relics, a vital aspect of medieval Christianity. Relics were understood to be material objects with a connection to a saint, ranging from bits of cloth to actual

bones or tissue from their body (Brown 1981). Because of this holy association,

relics had the potential to perform miracles, as evidenced by the myriad medieval

stories of their wonder-working.4

It is no surprise, then, that relics were used as devotional tools for medieval

Christians. Saint Ursula was of particular importance in medieval Cologne, because

according to her legend, she and her companions had been martyred there

by the

Huns.

Though this hagiographical tale had been in circulation since at least the fifth

century, the discovery of a Roman cemetery in Cologne near the site of a church in

their honor in 1106 was seen as definitive proof of Ursula’s story (Holladay 1997,

72). More importantly, this cemetery provided an unprecedented number of holy

relics, launching the mass production of the Ursula busts under study here.

These busts remained remarkably similar over the course of the two centuries in

which they were most prodigiously produced (cf. figure 1-3).

Figure 3: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1340

Carved in wood, usually walnut, most of the busts are roughly life-sized, measuring between 40 and 50 centimeters in height (Bergmann 1989, 287pp). The majority of the medieval busts are of women, but some also depict men and even children who, according to the legend, were inspired to join Ursula’s group of travelers. The faces of the busts are often carved with narrow eyes, a smiling mouth, and a wide nose, and are painted in tones that imitate human flesh. The hair and clothing are usually finished with gold detailing, and many of the busts also include a trefoil or quatrefoil opening through which the relics within would have been visible. They also include the skull relic within the head of the carved figure, accessible via a hinged lid that forms the crown of the head.

Acting as the “faces” for the relics within, these anthropomorphic sculptures took

an active part in the devotional and liturgical life of the medieval church. The

largest single group of these bust reliquaries was housed at the Church of Saint

Ursula, and within this sacred space they were frequently on the move, carried in

procession, placed on altars, and even taken to the city walls to protect Cologne.

Like puppets, then, these busts combined an anthropomorphic appearance

with mobility – that is, their mimesis of the human was both visual and kinetic.

At the same time, however, we must keep their object status in mind. Indeed,

evidence indicates that medieval viewers – from their creators to the laity that

encountered them – were well aware that these sculpted busts were inanimate

objects, no matter the divinity imputed to them by virtue of the relics they contained.

In short, these busts encouraged their audience to see them with “double

vision” – as both perceived objects, and as imagined lives.

Life and its lack: the tension of the Ursula busts

Figure 4: Detail of Figure 2, showing opening with visible relicswith visible relics.

Recent scholarship on the Ursula busts has sought to understand how the

appearance

of these busts may have affected the ways they were used. Joan

Holladay

has suggested that the lifelike appearance of the busts was intended

to make them “appear more human and approachable,” representing a community

of female saints with which viewers could connect on a more intimate level

(Holladay 1997, 88). The busts’ emphasis on the humanity of

the saints also contributed to their idealization by Cologne’s

Christians, and women in particular, in what Scott Montgomery

calls imitatio Ursulani (Montgomery 2010, 45). For both

of these scholars, then, the Ursula busts’ imitation of the human

form served as a means of connecting with their viewers.

Imitation, however, is a fraught endeavor. On the one

hand, the Ursula busts do an impressive job of suggesting fleshy

humanity. Their rosy cheeks suggest blood pumping below the

skin, and the small smiles gesture to an emotional inner life.

Furthermore, though the busts share many common features,

they do also include enough variations to suggest their individual

differences, from the placement of the eyes on the face, to

dimpled chins, and a variety of hairstyles (cf. figure 1-3).

In spite of this apparent liveliness, however, the busts constantly undermine their own illusionism. Portraying only the upper half of the body, the bust form itself proclaims its incompleteness, and thus its lack of real life. It also asserts itself not as life but as object in the way that it provides visual access to the relics it contains within, by means of trefoil and quatrefoil openings that pierce the chest of many of these busts (cf. figure 1-4).

Figure 5: View of the Goldene Kammer, St Ursula, Cologne; arrangement dating to 1643.

These openings reveal two contradictory

things at once: first, that no matter how lifelike

they appear, these busts are pieces of wood;

and second, that though they are only wood,

they in fact contain pieces of the real body of

the saint. The artificial and the real, and the

inanimate and the animate, are held in permanent

tension.

This tension is evident, too, in the ways

in which these busts were displayed in the

church, and particularly in the room known as

the Goldene Kammer (cf. figure 5).

Located off the church’s narthex, this

rectangular space today contains over one

hundred reliquary busts, many of which are

medieval in date (Urbanek 2010). Though the

present arrangement dates to 1643, sources indicate

that the busts were displayed en masse

in a similar manner as early as the fourteenth

century (Legner 2003, 208). Medieval visitors

to the church, then, would have encountered

these busts as an impressive group. Displayed

in such a manner, the stylistic and formal differences

between the busts are mostly subsumed

to a sense that they all belong to the same

group (Montgomery 2010, 64p.). Similarly, this

group display had a theological purpose, suggesting

a corporate model of sanctity, as Holladay has argued (Holladay 1997, 94). To this I would add its aesthetic impact:

presenting this coherent company would also have visually undermined the sense

that these were “real” people, thereby calling attention, once again, to their status

as objects, as representations of the saints. Once again, the busts juxtapose life

and its lack, encouraging double vision.

This juxtaposition of the animate and the inanimate would have been even

more pronounced in those instances in which these busts acted as mobile agents,

both within and outside of the church. Within the church, they took part in the dynamic

environment of this sacred space. The interior of the medieval church was

constantly changing throughout the liturgical year, from the rotation of textiles,

to the regular opening and closing of altarpieces, and the periodic display of reliquaries,

chalices, and crosses on the altar for feast days.5 Given the importance of

the cult of St. Ursula to Cologne, and to the church that bears her name, it seems

highly likely that some of these bust reliquaries, too, may have found their way to

the high altar on the feast of St. Ursula, and possibly other major feast days. While

the actual physical movement of the busts to and from the altar would likely only

have been witnessed by a few clerics, their appearance and disappearance would

have been more widely noted as an indication of the busts’ mobility and their

position as “stand-ins” for the saint(s).

The Ursula busts were also moved in ways that brought them outside of the

church and into the civic realm of medieval Cologne. Processions with relics were

a common feature of Christian practice in the Middle Ages, and there is ample

evidence of this practice occurring in Cologne (Kroos 1985, 39p.). Once again,

because of the importance of the Ursula relics to the city, it is probable that on

some occasions, the busts holding many of these relics would have been involved

in such processions. This likelihood is further supported by an account of a procession

dating to 1607, in which the busts were taken from the Goldene Kammer

by young, aristocratic women wearing “golden garments,” who then carried them

around the church and through the cemetery (Holladay 1997, 88p.). Though this

account documents a post-medieval practice, Holladay has convincingly argued

that this event was part of a long-standing tradition of processing with busts that

could have begun as early as the thirteenth or fourteenth centuries (ibid., 89).

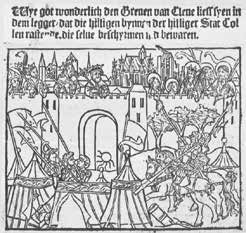

Figure 6: Johann Koelfoff; Cronica von der hilliger Stat van Coellen, 1499

Whether or not we can read this early seventeenth century event backwards into

the period under study here, it seems likely that the busts would have been involved

in some processions. In these events, double vision would have been in

full effect, as the lifelike busts moved through the church and into the city, juxtaposed

with the “real” live bodies of those who carried them. Here, the “imagined

life” of the reliquaries would have been suggested both by their movement and

their physical features, while their object status remained on display, particularly

because this movement relied on the intervention of human agents. Therefore,

the use and appearance of the reliquary bust amplifies the tension between the

animate and the inanimate, simultaneously affirming and destabilizing its ability

to present the real presence of the saint.

However, it is important to note that this destabilization did not prevent the

saint from acting through this sculpted bust, as is evident in the use of these busts

in an incident in 1268. In this year, the city of Cologne was attacked by the forces

of Archbishop Engelbert II von Falkenstein, but according to legend they were

repulsed with the aid of the city’s patron saint, Gereon, as well as Ursula and her

Virgins (Montgomery 2010, 102p.). A 1499 woodcut illustration of this attack

depicts this moment in a telling manner: here, the city’s saintly protectors are

depicted

on the right side of the city walls, identifiable by their haloes (cf. figure 6).

While the three saints on the far right –

Gereon, Severinus, and a companion – are

shown from the waist up, as if standing

behind

the crenellations of the wall, the two

female

saints are depicted as busts. Holladay

suggests that this could reflect a practice

in the late fifteenth century or earlier of

bringing the busts from the church to the

ramparts

in times of danger (Holladay 1997,

80). Given that this use of reliquaries is well

attested in other contexts, her argument is

convincing, and provides another example

of how the busts were understood both as

objects and as lives, able in this physical

form to provide aid.

Indeed, the artist’s choice to render Ursula and her companion differently than

the other patron saints of the city suggests that for him – and for the presumed

readers of the chronicle in which this illustration is found – the busts were a

recognizable sculptural form, through which divine presence could act. In other

words, the Ursula

busts had the potential to bridge the gap between the earthly

and the divine; their “puppet performance” could mediate between God and man.

Figure 7: Reliquary casket; Limoges (France), c. 1200-1220.

Relics, reliquaries, and double vision

The evidence of the 1499 woodcut indicates that medieval viewers saw no conflict

in the idea that inanimate (yet lifelike) objects could function efficaciously as

stand-ins (or, indeed, act-fors) for the saints they represented. Their combination

of two apparently contradictory ontological states – the inanimate and the animate

– was therefore not something that needed to be overcome, or even overlooked.

The double vision inspired by these busts did not detract from their efficacy.

Here again, puppetry provides a way to analyze the positive potential of

this play with boundaries. As Tillis suggests in his concept of double vision,

the puppet “pleasurably challenges” its audience to consider the binaries that it

questions. The notion of pleasure is crucial here, both for the puppet and for the

Ursula busts, because it suggests that the indeterminacy of such objects can be

productive, leading the audience to deeper reflection. Such reflection takes on a

special meaning for the Ursula busts, the primary function of which was to hold

relics. The relics contained in these busts were actual pieces of dead bodies, often

including entire skulls as well as smaller bones and fragments (Bergmann 1989;

Urbanek 2010). At the same time, however, the doctrine of bodily resurrection

attributed

holy animacy to the relics. This doctrine holds that a reunion of the

physical body and the soul will occur on the day of the Last Judgment. Prior

to that time, the bodies of normal humans would decay, while their souls lay

dormant in anticipation of the end times. The souls of saints and martyrs, on the

other hand, were believed to have been resurrected upon their death, skipping

the wait to join God because of their remarkable favor in his eyes. This primary

resurrection

was not a corporeal one, but it was understood that the bodies of

these

saints – and, by extension, their relics – acted as a direct link to God in

heaven, as the spirits that were so irrevocably linked to these bodies were already

there (Brown 1981, 72). Herein lies the ontological paradox: relics were simultaneously

dead matter, and part of an eternal, living body.

In addition, the relic embodies a representational paradox, and it is here that the

reliquary plays an important role. From a strictly materialist perspective, relics

are simply bones. Like the consecrated host, their outward appearance provides

no indication of their actual divine status as a part of the to-be-glorified body of

the saint (Geary 1991, 5). As the cult of relics developed, the reliquary emerged

as a means of communicating the theological truth of the relic. Eventually, the

reliquary became so essential to this task that canon 62 of the Fourth Lateran

Council in 1215 decreed that “old relics may not be exhibited outside of a vessel.”6

These reliquaries took a wide variety of forms, including caskets, purses, architectural

shrines, and figural forms such as arms, feet, and heads.7

No matter its form, the reliquary acted as a framing device that signaled the

preciousness of its relics. It often accomplished this task through a combination of

precious materiality and craftsmanship. For example, a French reliquary châsse

dating to the first quarter of the thirteenth century communicates its value not

only through the use of gold, but also through the tricky, expensive technique of

enamelwork (cf. figure 7).

Here, the value of the relic it contained is signaled

by means of an analogy, wherein the high

terrestrial value of these materials parallels the

high celestial value of the relics. This analogy

could also work on another level. Brigitte

Buettner has suggested that these precious materials

performed two related functions: first,

they signaled the preciousness of the relics,

and second, they inspired the beholder to recognize

the inferiority of these same materials

in comparison with the relics contained therein

(Buettner 2005, 57).

Figure 8: Bust reliquary of St. Baudime; French (Auvergne), mid-12th century.

This logic can be found in both non-figural

and figural reliquaries, including head reliquaries.

The reliquary bust of Saint Baudime,

for example, dating to the second half of the twelfth century, is made of copper

gilt applied to a wooden core, with

details of its clothing decorated by

gemstones, and its eyes rendered in

ivory and horn (cf. figure 8; Boehm

1990, 285pp.).

As it did with non-figural

reliquaries,

this golden exterior no

doubt caused the viewer to reflect

on its value, and then on the value

of the relics it held. However, the

humanoid form adds another interpretive

layer, suggesting not only the

heavenly power of the relic, but also

the reality of its bodily presence. A

golden bust reliquary like that of

Saint Baudime thereby communicates

not only the value of the relic, but

also the truth of bodily resurrection.

In a sense, it pictures the saint in his

future glory, his body transformed

by the divine from the dead, decaying

stuff of death to the incorruptible

materiality of eternal life (Legner

1995, 257; Fricke 2007, 145).

At the same time, however, one must acknowledge that the glittering materiality

of Baudime’s bust also served to undermine the reality of its bodily presence.

Double vision is in evidence here, too, as the life suggested by details like

Baudime’s carefully stippled beard and striking eyes is interrupted by the obvious

artificiality of its metal skin. This bust seems to exist in a space and time separate

from our own, as signaled by its piercing, unfocused gaze, and the frozen gestures

of its hands. These aesthetic choices contribute to a theological aim, in which

this bust represents the future reality of the saint, who will indeed exist outside

of space and time as we know it. Here, then, the ontological musings inspired by

double vision relate primarily to the distance between the earthly and the divine.

The Ursula busts, by contrast, are crafted out of materials without self-evident

terrestrial value. To be sure, many of these figures still use gold, but it is

predominantly used in naturalistic ways, as for example in the details of clothing.

Even the detail of gilding the hair of these busts has a naturalistic bent, suggesting

light playing on blond or light-colored hair (cf. figure 3). The overall impression

of these busts is of real, fleshy humans, not so far removed from the medieval viewer

who contemplated them. Yet, as I have demonstrated, this impression of life

is consistently undermined in the many ways that these busts were used and encountered.

How, then, do these busts use this double vision to explore the paradox

of the relic?

To answer this question, we must return again to what puppetry can tell us

about aesthetic choice. When a maker designs a puppet, he/she makes both aesthetic

and mechanical choices; for example, he/she must decide if it will be operated

with an internal rod (a rod puppet), or with strings from above (a marionette).

He/she must then also decide its humanoid features: will these be comically exaggerated,

generic, or stylized? Each of these choices in turns determines the kinds

of stories and effects the puppet will have. As Basil Jones writes, these form the

puppet’s “meta-script,” which dictate, at least in part, how a puppeteer can use

the puppet effectively, and what kinds of meanings it can successfully convey

(Jones 2014, 64). The meta-script of the Ursula busts indicates that the primary

meanings they were intended to communicate relate to the tension between the

animate and the inanimate.

This tension is heightened in those cases where the Ursula bust provided

visual access to the relics it contained through trefoil and quatrefoil openings

(cf. figure 4). The juxtaposition of the carved and painted face with actual bones

could assert a potential corporeal likeness: beneath this artificial face are real

bones. The relationship between the artificiality of the bust and the reality of the

bones would have been further complicated by the obvious beauty of the painted

face, in contrast to the unremarkable appearance of the fragments of bones. Yet

again, this object makes clear that appearances – and by extension, the senses –

can be deceiving, particularly when it comes to sacred things.

Like reliquaries made of more precious materials, then, the wood-and-polychromy

of the Cologne Ursula busts teach the viewer a theological lesson

about the limits of human perception with regards to the divine. For these

reliquaries, it is not the preciousness of the materials but the suggestion of human intimacy that first attracts the viewer. Like the precious materials,

however, this attraction is not where the true value of this object lies; rather, it

is contained within, in the relics of the saints. As I have argued, this was also

the effect of all reliquary busts; what sets the wood-and-polychromy Ursula

busts apart from other reliquary busts is that this tension relied entirely on the

simultaneous suggestion and denial of the human. These busts thus evidence

a medieval engagement with the inherent paradox of representation as a devotional

tool.

Understanding the Ursula busts as analogous to puppets allows us to see these objects

as sites of encounter between the divine and the human. To be sure, the relics

held inside these busts also offered this possibility. However, the bust reliquary

frames this space of encounter as analogous to a human life, one with which the

human user could communicate. This suggestion, however, is undercut by the

recognition that it is, in fact, not human – and not alive – at all.

While this realization might seem threatening to some, the framework of

puppetry suggests a different outcome for this destabilization of boundaries. The

liminality of the Ursula busts provided access to the divine. To argue that the bust

reliquary is analogous to the puppet, then, is to argue that it was a mimetic tool

deployed deliberately for its in-between status. As John Bell writes, the essence

of the puppet “is not mastery of the material world, but a constant negotiation

back and forth with it” (Bell 2014, 50). The Ursula bust reliquary, too, calls into

question the real and the copy as it simultaneously affirms and denies its animation,

both in appearance and in use. The tension between appearance and reality

– the paradox of representation itself – is at the root of these liminal objects. Like

the puppet, the Ursula busts suggest life, but time and again they reveal themselves

to be mere things. Ultimately, this denial has theological power: though the

busts might not be the saint, they still provide access to the saint – not by virtue of

their crafted faces, however, but by the relics hidden within. The tension between

the illusionism of the bust and its obvious object status, then, calls attention to and

amplifies the tension of the relic itself.

Conclusion: Productive mimesis

I have demonstrated how the lens of puppetry can help us understand a group of

objects from medieval Cologne, a world both temporally and conceptually removed

from our own. The framework of puppetry has provided a way to think

about how the form and function of the Ursula busts worked in tandem to create

a devotionally

valuable object. Furthermore, this framework has suggested that

these reliquaries were useful not in spite of their status as material representations,

but because of it. Puppetry thereby offers a different assessment of the value

of mimesis

than that usually attributed to the medieval world.

Christianity’s official stance on the value of representation has always been

fraught. Two major philosophical strains are at the heart of representation’s ambivalent

status: first, the biblical prohibition against images of the divine, as

expressed

in the Second Commandment, and second, Christianity’s inherited

Neoplatonism, which understood images as degraded copies of the Real (Wildberg

2019). As a result, there was a persistent anxiety about the function and

dangers of representation. The work of the art historian Michael Camille, in particular,

traces the idea that representation was conceived of as a “sinister magic” in

the medieval period (Camille 1989, 62).8 The feelings of ambivalence and anxiety

that images clearly inspired in the medieval period are an important field of study,

and there is still much to be explored in particular about how medieval laypeople

wrestled with this anxiety – both with regards to theater, and to the visual arts

– in their daily practices. However, the example of the Ursula bust reliquaries

suggests that the act of mimesis – of imitation, representation, and reproduction –

also served a productive purpose within the Christian framework.

The idea of mimesis as “sinister magic” did not end with the Middle Ages,

however. Indeed, as the religious reformations of the sixteenth century swept

through Europe, the role of representation in Christian practice – both visual and

theatrical – was radically reevaluated.9 Even today, mimesis is often approached

with ambivalence, revealing a continued concern about the lines between the real

and the copy, and the animate and the inanimate.

Technological innovations in artificial intelligence (AI) have once again

brought this ambivalence to the fore of Western culture. Popular representations of AI suggest the same discomfort with hybridity that was implied by Pinocchio’s

laughter; as one scientist remarked in 1996, “[m]achines, even in our homes, will

become so intelligent that they may become our tyrannical masters” (Bloomfield

& Vurdubakis 1997, 39). Such dystopian visions, in which increasingly sophisticated

machines will, in the end, destroy humanity, are not uncommon, and reveal

a new way of expressing an old concern about mimesis, that somehow the “copy”

will overtake or degrade the “original.”

However, other interpreters see in AI a new way forward, in which the dualism

of human and machine exists not in opposition, but in an emergent balance.

This strain of thought is generally associated with “posthumanism,” to borrow

N. Katherine Hayles’ term, which posits that humans and machines both will be

so radically transformed by technological advances that there will be little use in

trying to separate the one from the other (Hayles 1999). The posthuman, then,

will be both human and machine, or indeed, neither human nor machine. Out of

this hybridity, furthermore, arise new potentialities for (post)humanity.

Through the framework of puppetry, we can see how the gap between

posthumanism and the reliquary busts of medieval Cologne is far smaller than

one might imagine. The imagined lives of the Ursula busts are produced through

the improvisatory, innovative, and fundamentally destabilizing hybridity of the

puppet, which depends on a close interaction between inanimate, crafted objects

and animate humans. In a similar manner, the play between the animate human

and the manmade machine creates the “life” of AI. What this suggests, then, is

that reflection on our own ambivalences toward mimesis is necessary for exploring

AI’s potential, not simply as a technological innovation but as a philosophical

and cultural force. Just as the materiality of the reliquary bust challenged its

viewers to reflect on powers beyond human understanding, so too can the liminal

status of AI provide an opportunity for us to challenge and transform our own

assumptions about the artificial and the real, the animate and the inanimate, and,

indeed, what it means to have life.

[1] This article is derived from a chapter of my dissertation, so I would like to thank my advisor, Jacqueline Jung, for her invaluable feedback during the writing process. In addition, I must also thank J. Christian Greer and Lynna Dhanani for their feedback as I crafted this article.

[2] Puppetry’s marginalization in Western culture has been traced in detail in Shershow (1995). I explore historiography of this marginalization in greater depth in the introduction to my dissertation (Oing 2020), which may be consulted for further information.

[3] Earlier legends spoke of Ursula’s eleven companions, but this number increased a thousandfold by the ninth and tenth centuries, probably due to a misreading of a Latin inscription (cf. Holladay 1997, 72).

[4] Foundational texts on the study of the medieval cult of saints include Brown (1981) and Geary (1978).

[5] For an overview of the changing displays in medieval churches, see Snoek (1995).

[6] “…reliquiae amodo extra capsam nullatenus ostendatur.” As quoted in the Internet Medieval Source Book (1996).

[7] For more on this range of forms, see Hahn (2012).

[8] A number of medievalists have explored expressions of this anxiety towards images in the Middle Ages. In addition to Camille, see also Belting (1990), Bynum (2011), and Freedberg (1989).

[9] On the changing place of the image in Reformation Europe, see Koerner (2004) and Michalski (1993).

References

Primary LiteratureThe Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215. Halsall, Paul (Hg.), The Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

Accessed 10 October 2019. Retrieved from:

Collodi, Carlo (1883). The Adventures of Pinocchio (translated from Italian by Geoffrey Brock). New York: New York Review of Books, 2009.

Secondary Literature

Bell, John (1996). Death & Performing Objects. P-Form, 41, 16-20.

Bell, John (2014). Playing with the Eternal Uncanny: The Persistent Life of Lifeless Objects. In Dassia N. Posner, Claudia Orenstein, John Bell (Hg.), The Routledge Companion to Puppetry and Material Performance (pp. 43-52). Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Belting, Hans (1990). The Image and its Public in the Middle Ages: Form and Function of Early Paintings of the Passion. (Translated from German by Mark Bartusis and Raymond Meyer). New Rochelle, NY: A.D. Caratzas.

Bergmann, Ulrike (1989). Kölner Bildschnitzerwerkstätten vom 11. bis zum ausgehenden 14. Jahrhundert. In Anton Legner (Hg.), Die Holzskulpturen des Mittelalters (1000-1400) (S. 19-63). Köln: Das Museum.

Bergmann, Ulrike (1996). St. Ursula, Goldene Kammer. In Margrit Jüsten-Hedtrich (Hg.), Kölner Kirchen und ihre mittelalterliche Ausstattung, Bd. 2, Colonia Romanica XI (S. 225-231).

Bloomfield, Brian P., Vurdubakis, Theo (1997). The Revenge of the Object? On Artificial Intelligence as a Cultural Enterprise. Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology 41.1, 29-45.

Boehm, Barbara Drake (1990). Medieval Head Reliquaries of the Massif Central. Diss., New York University.

Brown, Peter (1981). The Cult of the Saints: Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Buettner, Brigitte (2005). From Bones to Stones – Reflections on Jeweled Reliquaries. In Bruno Reudenbach, Gia Toussaint (Hg.), Reliquiare im Mittelalter (S. 43-59). Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Bynum, Caroline Walker (2011). Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe. New York: Zone Books; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Camille, Michael (1989). The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Craig, E. Gordon (1908). The Actor and the Über-Marionette. The Mask: A Monthly Journal of the Art of Theatre 1(2), 3-15.

Freedberg, David (1989). The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Fricke, Beate (2007). Entlarvende Gesichter – Gedanken zur Genese der Kopfreliquiare in Italien. In Jeanette Kohl, Rebecca Müller (Hg.), Kopf/Bild: Die Büste in Mittelalter und Früher Neuzeit (S. 133-152). München; Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag.

Geary, Patrick (1991). Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hahn, Cynthia (2012). Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400-circa 1204. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Hayles, N. Katherine (1999). How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Holladay, Joan A. (1997). Relics, Reliquaries, and Religious Women: Visualizing the Holy Virgins of Cologne. Studies in Iconography, 18, 67-118.

Jones, Basil (2014). Puppetry, Authorship, and the Ur-Narrative. In Dassia N. Posner, Claudia Orenstein, John Bell (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Puppetry and Material Performance (S. 61-68). Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge.

Kang, Minsoo (2011). Sublime Dreams of Living Machines: The Automaton in the European Imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kleist, Heinrich von (1810/2007). Über das Marionettentheater. In Wolfgang Kurock, (Hg.), Puppen & Masken. Frankfurt a. M.: Verlag Wilfried Nold.

Koerner, Joseph Leo (2004). The Reformation of the Image. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kroos, Renate (1985). Vom Umgang mit Reliquien. In Anton Legner Anton (Hg.), Ornamenta Ecclesiae: Kunst und Künstler der Romanik, Bd. 3 (S. 25-49). Köln: Stadt Köln.

Legner, Anton (1995). Reliquien in Kunst und Kult: zwischen Antike und Aufklärung. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Legner, Anton (2003). Kölner Heilige und Heligtümer: ein Jahrtausend europäischer Reliquienkultur. Köln: Greven.

Michalski, Sergiusz (1993). The Reformation and the Visual Arts: The Protestant Image Question in Western and Eastern Europe. London; New York: Routledge.

Montgomery, Scott B. (2010). St. Ursula and the Eleven Thousand Virgins of Cologne: Relics, Reliquaries, and the Visual Culture of Group Sanctity in Late Medieval Europe. Oxford; New York: Peter Lang.

Oing, Michelle (2020). Puppet Potential: Visual and Kinetic Mimesis in Late Medieval and Early Modern Sculpture. Diss., Yale University.

Proschan, Frank (1983). The Semiotic Study of Puppets, Masks, and Performing Objects. Semiotica 47 (1-4), 3-44.

Rath, Markus (2017). Die Gliederpuppe: Kult, Kunst, Konzept. Boston: De Gruyter.

Schechner, Richard (2003). Actuals. In Richard Schechner (Ed.), Performance Theory. London; New York: Routledge.

Schneider, Rebecca (2014). Theatre & History. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shershow, Scott (1995). Puppets and ‘Popular’ Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Snoek, G. J. C. (1995). Medieval Piety from Relics to the Eucharist: A Process of Mutual Interaction. Leiden; New York: E. J. Brill.

Tillis, Steve (1992). Toward an Aesthetics of the Puppet: Puppetry as a Theatrical Art. New York: Greenwood Press.

Urbanek, Regina (2010). Die Goldene Kammer von St. Ursula in Köln: zu Gestalt und Ausstattung vom Mittelalter bis zum Barock. Worms: Wernersche Verlagsgesellschaft.

Wildberg, Christian (2019). Neoplatonism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed 5 June

2019. Retrieved from:

List of Figures

Figure 1: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1330/40; oak, walnut, and polychromy; 47 x 38 x 22 cm,; Goldene Kammer, Church of St. Ursula, Cologne, Germany. Photo by author.

Figure 2: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1350; oak, walnut, and polychromy; 62.5 x 34 x 31 cm.; Goldene Kammer, Church of St. Ursula, Cologne, Germany. Photo by author.Figure 3: Reliquary bust of a companion of St. Ursula, c. 1340; walnut, polychromy; 51 x 26.5 x 24 cm.; Museum Schnütgen, Cologne, Germany. Photo by author.

Figure 4: Detail of Figure 2, showing opening with visible relics. Photo by author.

Figure 5: View of the Goldene Kammer, St Ursula, Cologne; arrangement dating to 1643. Photo by author.

Figure 6: Johann Koelfoff; Cronica von der hilliger Stat van Coellen, 1499, (“Defense of Cologne on October 14-15, 1268”); Kölnisches Stadtmuseum, Cologne. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne. RBA_mf091133. Retrieved from: < https://www.kulturelles-erbe-koeln.de/documents/ obj/ 05203804 >

Figure 7: Reliquary casket; Limoges (France), c. 1200-1220; copper and champlevé enamel; The

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913. Retrieved from:

Figure 8: Bust reliquary of St. Baudime; French (Auvergne), mid-12th century; copper-gilt over walnut core, ivory, and horn; Mairie de Saint-Nectaire, France. Credit: © bpk Bildagentur / Art Resource, NY.

About the Author / Über die Autorin

Michelle OingMellon Fellowship of Scholars in the Humanities, Stanford University, 2020- 2022; PhD History of Art & Architecture, Yale University, 2020; M.Phil. and MA History of Art & Architecture, Yale University; M.T.S. History of Christianity, Harvard Divinity School; B.A. History of Art & Architecture, Brown University; publications on “Holy Puppets” and “Votive Bodies”; several awards, honors and invited lectures; teaching, research and museum experience.

Correspondence address / Korrespondenz-Adresse:

mkoing@stanford.edu