denkste: puppe / just a bit of: doll | Bd.5 Nr.1 (2022) | Rubrik: Fokus

Can one squander their purest affections on gruesome foreign bodies? Remarks on the doll motif in the oeuvre of Marek Piasecki

Marta Smolińska

Focus: Narrative, Botschaften und visuelle Ästhetik figürlicher

Puppen in Mode, Kunst, Fotografie und Film

Focus:

Narratives, messages and visual aesthetics of figurative

dolls/puppets in fashion, art, film and photography

Abstract:

ABSTRACT (English)

The 1950s and 1960s series of black-and-white photographs by the Polish artist

Marek Piasecki (1935-2011) entitled The Doll as well as the objects created in

the same period in which the artist wove the motif of a doll are analysed in the

context of the doll text by Rainer Maria Rilke and the work of Hans Bellmer, complemented

by reflections by Anna Szyjkowska-Piotrowska, Georges Didi-Huberman and other

contemporary authors. Fragmentation of bodies in these works by Piasecki is not a device

of eroticization or fetishization, as in Bellmer, but makes one aware of their defenceless

fragility and mortality. As a typical abject Piasecki’s doll attract as much as they put one

off; their presence verges on unbearable as it awakens the anxiety of death.

Keywords:Marek Piasecki, doll, photographs, objects, abject

How to cite: Smolińska M., Can one squander their purest affections on gruesome foreign bodies? Remarks on the doll motif in the oeuvre of Marek Piasecki, v. 5, n. 1, p. 18-25, 17 Okt. 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25819/dedo/135

Copyright: Marta Smolińska. Dieses Werk steht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de).

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/9992

Veröffentlicht am: 17.10.2022

Um auf Zusatzmaterial zuzugreifen, besuchen Sie bitte die Artikelseite.

Who do I trust – Piasecki, Rilke …?

The 1950s and 1960s series of black-and-white photographs by Marek Piasecki1 entitled The Doll (cf. figures 1-15) as well as the objects created in the same period in which the artist wove the motif of a doll convinced me not to trust Rainer Maria Rilke. In 1914, the Austrian poet wrote in his famed Puppen. Zu den Wachs-Puppen von Lotte Pritzel [Dolls. On the Wax Dolls of Lotte Pritzel]that they have neither soul nor imagination and, unlike marionettes, rank lower in hierarchy than things (Rilke 1994, 3). Moreover, they are typified by “the gruesome foreign body, on which we squandered our purest affection; as the superficially painted watery corpse borne up and carried along on the floodwaters of our tenderness until we were on dry land again and abandoned it in some thicket” (Rilke 1994, 3). Rilke continues: “a poet could fall under the domination of a marionette, because the marionette has only imagination. The doll has none, and is exactly that much less than a thing as the marionette is more. But this being less than a thing, in all its inevitability, contains the secret of the doll’s predominance” (Rilke 1994, 4). Furthermore, it must be remembered that using the doll motif was a bold move, as Piasecki did so after Bellmer’s works and publications in the 1930ies, which was by no means a minor challenge. Most likely, he found his dolls in the attics and at flea markets. Then, not only did he photograph those objets trouvés, but also assembled them into objects in the privacy of his successive studios, only to capture them on black-and-white film again. What was it that he managed to extract from the doll in the staged analogue photographs, objects and photographed objects which differed from what Rilke and Bellmer saw in them? What narratives involving dolls did he visually construct?

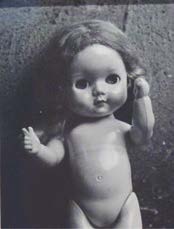

Piaseck’s dolls – ambivalent and decultured

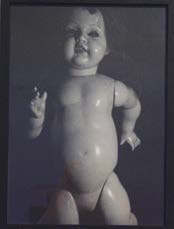

I would be tempted to say that Piasecki permanently imbued those horrifyingly alien bodies with soul and imagination, elevating them above objects (cf. figures 1, 4, 5, 8). It was he who caused them to look at us so vividly that we see ourselves anew,

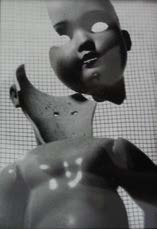

Figure 1: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 4: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 5: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 8: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

arrested by their penetrating gaze that has us transfixed in front of the photographs.

We feel uneasy, as if we were sinking into the Freudian das Unheimliche – the

uncanny, a psychoanalytical notion which expresses the sense of perplexity or fear

when facing a known phenomenon which suddenly appears alien, mysterious and

intriguing. In Piasecki’s images and objects the doll is both

terrifying and rivets one’s attention; it is simultaneously

ordinary and familiar as well as astonishing. As such,

it is in line with the Surrealist and neo-Dada traditions,

though its semantic saturation substantially exceeds both

of those contexts. This is the case even with seemingly

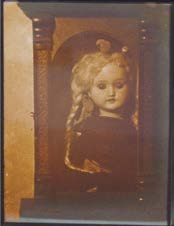

classic portraits of dolls (cf. figures 2, 6).

As Hans Bellmer observed with respect to sharply focused

images, this unnatural vividness could no doubt have

been enchanting and captivating. The dolls in Piasecki’s

works are undoubtedly enchanting and singularly distorted

out of their natural form or – as I would put it – deculturated.

After all, their nature, shaped within the realm

of culture, assumes a highly peculiar aspect in the blackand-

white photographs and in the objects. Quite certainly

they are no innocent child’s toys which girls carry around

in the toy prams among frilly cushions. In most cases,

they remain naked and fragmented, inhabiting confined,

tight and “stuffy” frames. They arouse disquiet rather

than pacify. They possess both soul and imagination. As

Rilke further underlines –oppositely this time: “we could

not make it into a thing or person, and in such moments

it became a stranger to us” (Rilke 1994, 4). Thus, it functions

in-between and its status is unresolvable, which

leads to ontological and epistemological indeterminacy.

For his part, Bellmer, that profound connoisseur and

passionate aficionado of doll-ness observed that a doll is

only alive thanks to ideas with which it is infused. Piasecki

filled his dolls with notions to the brim, hence their

poignant effect on our imagination whereby all sorts of

clichés are elicited from memory. The artist dressed the

dolls, arranged, posed, illuminated and photographed them, while stripping them

of the carefree infantility. According to Bellmer despite boundless submission

there is an utterly exasperating distance in those dolls. As Paul Éluard writes in

the series of prose poems entitled Les Jeux de la Poupée (1949), the doll scares

animals and children… among the sheets is where its mirror lies. In the case of

works by Piasecki, we – the viewers – serve as the mirror and one cannot deny

that there is something uncanny in that confrontation. The gazes of an artificial

and a living body interlock, asking one another about their respective conditions.

Piasecki frames his photographs in such a way that the doll is most often shrunken,

as everything that may be said of it reduces and confines it. In the smallest

space of the narrowest field of vision, we are looking – reckoning and arguing –

for a place where its heart is, assessing the faith in childhood.

Figure 2: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 6: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

A face behind the face – between post-face and mask

One would like to say that Piasecki’s dolls do not have faces but rather a symbolic and discursive post-face. Anna Szyjkowska-Piotrowska, author of the monograph entitled Po-twarz. Przekraczanie wizualności w sztuce i fotografii [After-Face. Transgressing visuality in art and photography], notes that inherent in the nature of the word is a “rupture, which at the same time constitutes a juncture; it construes face as a ‘space between’ which harbours multiple dichotomies and yet manages to unite various oppositions of culture. In the ‘post-face’ one can see […] as we transcend face in its visuality heading towards the subsequent stadium of symbol, or watch how face slips away from our grasp” (Szyjowska-Piotrowska 2015, 6).

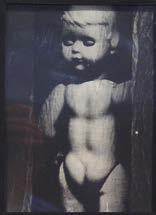

Figure 3: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 7: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

The physiognomies of Piasecki’s dolls are conventional, doll-like and repetitive,

while being individual and one of a kind at the same time (cf. figures 3, 7, 13, 15).

The artist knows perfectly how to play and animate the face as a space between

seriality and stereotype on the one hand

and idiosyncratic trait on the other.

Light, as it is juxtaposed with the dark, often

abysmal background, the framing and

the neighbourhood with another post-face

cause our encounter with those specific

dolls too be so laden with tension (cf. figures

10, 11).

Drawing on Giorgio Agamben, who

in his turn was inspired by a notion from

Walter Benjamin’s repertoire, I would say

that the visages of Piasecki’s doll have

an exposure value, being as immobile as

painter’s canvas. They operate in the realm between the post-face and a mask,

enabling us to attempt continual assessment of our faith in childhood. In the photographs,

that exposure value seems to be redoubled, as it is already contained in

the very frozen faces of the dolls, as well as in their posing for the artist, which

in its turn seems to stigmatize

the photographic medium itself.

The resulting effect is that of a

double exposure¸ though not in

the traditional understanding of

a photographic technique, but

a metaphor posing a question

about the visual phenomenon

of the intense presence of Piasecki’s

fanciful dolls. Photography

amplifies that exposure

value of the face, superimposing

its mediatic filter over it

and moving them into a sphere

of iconically dense image.

Figure 13: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 15: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

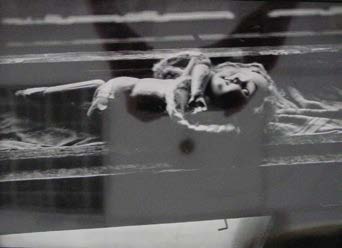

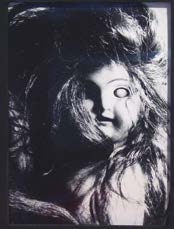

Spectre-dolls – vanishing to observe

Still, some among the dolls have closed their eyes, as if they rolled inwards and look into the back of their heads. Paradoxically, in those cases one has the impression that they observe us equally penetratingly with the unseeing eyes. Perhaps they sleep and dream, or perhaps they are irrevocably dead (cf. figures 5, 8, 9). Their physiognomies are thus even more post-faces or spaces in-between, while their exposure value is profoundly infected and permeated by das Unheimliche. If, one the other hand, one agrees with Georges Didi-Huberman who, inspired by fragments of Joyce’s Ulysses, asserted that seeing is a process of continuous loss, then one should close their eyes in order to see (Didi-Huberman 1999, 30f.). We are dealing with spectres we are able to see and who also see us. After all, Piasecki often relinquishes clarity and vividness in favour of vagueness and blurred contours – perhaps the dolls moved suddenly while posing and the motion was captured by the watchful camera? An aura of a kind arises around their sometimes twofold silhouettes, while the striation marking the direction of their supposed movement invest the entire composition with electrifying dynamism. There is a demonic and ghastly side to it, which Piasecki achieves using an opulent range of possibilities offered by photographic techniques.

Figure 10: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 11: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Figure 9: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

In order to enter into a dialogue with those spectre-dolls one cannot carry

out a metaphysical inquiry or essentialist investigation, but “learn to converse

with what is to be found in the undecided realm of ‘to be or not to be’. A spectre

does not have an established definition as it indulges in indeterminacy, resorts to

a violent breaking-and-entering, it is always an intruder (sans-papiers), therefore

it would be futile to ask it to produce an identity card” (Marzec 2015, 206-207).

Moreover, “we never encounter a spectre alone, they always come in droves, creating

societies and communities, hordes and packs” (Marzec 2015, 212). This

is exactly what happens in some photographs by Piasecki, where the dolls are

so ethereal as if they were only materializing or dematerializing, attracting our

eye with a transparency that sometimes yields the element of the background – a

luminous window with a tangible, black grille (cf. figure 14).

For a dialogue with the spectres in one’s own oeuvre, one has to come forward

with a thoroughly exceptional repertoire of visual devices. Hence Piasecki sets a

stage for the spectre-dolls, a setting in which they can make their appearance and

look at us so poignantly. Philosophers aptly note that “an apparition is impure,

indefinite, and construed only vaguely, fuzzily, and therefore it cannot claim notional,

fully accessible representation” (Marzec 2015, 133). Much the same applies

in visual arts. A spectre cannot attain a complete, saturated, convincing presence.

It has to merely – and as much as – manifest itself, remaining all the time on the

verge of vanishing. Insinuate its headless figure into our world, in this case into a

windowed room, to make its presence felt and then dissolve, leaving us changed

and haunted.

The doll, in itself a phenomenon of highly uncertain status, becomes additionally

ambivalent: it is incarnated into a spectre. Consequently, its identity is

even more inconclusive and fluid: “Spectres mock identity, since they are capable

of assuming any and changing it at will, masquerading as any subject, whose

boundaries thus unravel and become blurred, while the hitherto stable sense of

one’s existence is undermined” (Marzec 2015, 206-127). This, however, does not

attenuate the poignancy of the message they convey: they emerge from our own

memory, to tell us forcibly that our life is being-towards-death which, as if that

was not enough, takes place in times after the Catastrophe in Piasecki’s case.

One of the dolls has an unnervingly dismantled head, which appears shattered

and fragmented. The eye sockets are empty, while the body is exposed against

the backdrop of a sheet of paper with a regular, square ruling – as if the figure

was being subjected to some mysterious measuring or scaling (cf. figure 4). Ostentatiously,

the doll manifests its inner void, and yet it still possesses a soul.

Much the same happens with an object combining the rear section of the head of

some unidentified doll, as if the latter had been hollowed out, with a white, plastic

rabbit. The rabbit appears against the background of that empty “shell” like on

a stage and implies that something always remains inside, though the body may

be absent. Georges Didi-Huberman, who addressed seeing as a loss and disappearance

of things, concentrated on a volume comprising an empty space: what

kind of volume may demonstrate the loss of a body? What kind of volume can

harbour a void and be able to show it at the same time? (Didi-Huberman 1999, 31).

Figure 12: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll

Although the French historian and theorist of art deliberates on objects created

within minimal art, his intuitions are applied here to photography and objects

created by Piasecki, which in that very sensitive manner of theirs seek to pose

questions about the act of showing the void. Furthermore, following Didi-Huberman’s

line of reasoning, he asks immediately how one turns the act into a form,

a form which looks at and perceives us (Didi-Huberman 1999, 31). This hollowing-

out and inner emptiness may in fact affect any body, mine included, while

the work’s inevitable sense of loss is all the more vocal. With a humanoid doll, the

effect seems even more powerful than with the cubic forms of minimal art, such

as Tony Smith’s Black Box which Didi-Huberman analysed. The empty, gouged

sockets do perceive us; perhaps more potently than if the eyes were there. We are

looked at by the same emptiness with which Piasecki imbued the body of the doll,

a body defenceless and akin to ours. The entire photograph is an intense form,

which may be defined as a return of the repressed into the visual and aesthetic

sphere (Didi-Huberman 1999, 222).

The hair are also a highly disquieting element. Piasecki thus endows one of his

dolls with an opulent hairdo, perhaps even to an excess, which makes us ask

whether the hair of the character are its own or whether it is a sea of strange

hair it sunk into (cf. figure 9). Hair of such an ambivalent status and uncertain

link with a person become an oddity that can never be familiarized. As a typical

abject they attract as much as they put one off; their presence verges on unbearable

as it awakens the anxiety of death. The cut-off hair are haptic, seducing and

tempting the touch, yet the hand refuses to make contact. They are haunted and

spectral. In a viewer from Poland, the immediate association brings tons of hair

from Auschwitz to mind, triggering knowledge of the industry which used hair of

the Holocaust victims as raw material. The awareness translates into an atavism

which causes cut-off hair to be treated in a very singular manner, manifesting as

a fusion of fascination and abhorrence. Once cut off, hair becomes an unnatural excrescence, something which provokes disgust because it is a “detached part”

and an “early death” (Menninghaus 2003, 53). This is why that something is horrifying.

Disgust, as underlined by Friedrich Nietzsche and Jean-Paul Sartre later,

is nevertheless a token of genuine experience of existence, connoting the medium

of cognition itself, and enabling an insight into “the eternal essence of things”

(Menninghaus 2003, 9). The constricted, stifled frame, the closed eyes of the doll

and its parted lips add to the uncomfortable atmosphere. Even the flat photograph appears fleecy, tousle-haired and ruffled, just as the monstrous hair it shows. One

is tempted to state much the same as Éluard, saying that the doll is heavy, opaque,

coarse. In short, it is alone. Alone in its cold and clammy frame, alone and without

its eyes, inexorably alone. The only exception is that we are positioned directly in

front of it, which makes us realize our own condition. Deculturated and intensely

present, it will not let itself be ignored, since in the hierarchy of things it ranks

above objects and so close to us.

When Freud sought to justify the tendency to attribute life to inanimate objects (in his discussion of animism in Totem and Taboo), he quoted the following passage from the third section of Hume’s Natural History of Religion: “There is an universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves, and to transfer to every object those qualities with which they are familiarly acquainted, and of which they are intimately conscious.” (Freedberg 1989, 190).

Raised above objects – giving testimony of the human condition

Piasecki knew that dolls are worth

being dedicated his purest aspirations,

because then they would utter what

strikes our most sensitive spots and

concerns the most critical aspects of

the human condition, most often those

which are repressed. Fragmentation of

bodies is not a device of eroticization or

fetishization, as in Bellmer, but makes

one aware of their defenceless fragility

and mortality (cf. figures 4, 5, 12). Some of them are shattered, convulsive, while

the relations of body parts have nothing to do with anatomy, just as in Andrzej

Wróblewski paintings from the series Rozstrzelania [Executions]. The alignment

of arms and legs of one of the dolls resembles a running person – perhaps we see

her during some dramatic escape; another doll seems thoroughly immobile, dead.

In the objects-assemblages, fragments of bodies appear under glass domes, in cabinets which at times look like coffins, such as the red “rocket”, completing the

visual narrative of fragmentation which began in the black-and-white photographs.

In a 2005 poem entitled The House of Dolls Tadeusz Różewicz writes thus:

“[…] at night in the house of dolls / cries are heard and screaming / and the gnashing

of teeth […]”. In one of the objects-assemblages a solitary hand is a source of

horror: the hand stretches out towards the head which is severed from the rest of

the body too. The parts are chaotically intermingled with metal elements, bits of

tulle, cord, buttons and wires... Thus, the head and the arm have the same status

as the surrounding objects; the body is objectified and disintegrated, bearing

marks of violence. Another object features a naked, overturned torso, separated

from the rest and accompanied by a red sphere and bits of some matter.

The cabinet is constricted and oppressive. Since Piasecki’s dolls are by default

endowed by the artist with soul and imagination, this fragmentation is felt even

more acutely. They have already been raised above mere objects in hierarchy

and now, in these two works, parts of their bodies are suddenly elevated equally

high: the effect is all the more powerful and ghastly.

The backgrounds of photographs and objects-assemblages tend to be dark,

oneiric, indeterminate. Piasecki experiments with photographic techniques and

situates his dolls on what seems to be a juncture of darkness and our world,

enhancing their spectral nature and the exposure value of the physiognomies,

whose usually exaggerated and grotesque features draw the eye so much. In

turn, his play with chiaroscuro is as vivid as it was in Caravaggio and the Tenebrists.

By this means, we are even more emphatically introduced to the partners

in a colloquy in which voices may unexpectedly stick in one’s throat.

Conversations with the spectre-dolls are therefore neither easy nor pleasant.

Yet they foster an insight into the essence of one’s own existence, and

draw attention to the fact that “the present is not such a solid, homogeneous,

self-sufficient, cohesive and coherent actuality as may have seemed initially.

Spectres fracture and undermine the stability of ‘now’, revealing anachronicity

of reality and heterogeneity of time: the past is unwilling to go away and the

future does not want to come” (Marzec 2015, 193). The ghost of war and the

Holocaust is there to stay for certain as well. In a manner which is perhaps not

that obvious, It returns – albeit not that plainly – in the series of spatial compositions,

in which various forms, e.g. spheres, are put to display on cuboidal,

cylindrical or polygonal plinths, bringing miniature anti-monuments to mind.

Their impenetrable black and the mysterious, abstract form commemorate the

dramatic fates of dolls, whose bodies have been dismembered in the merciless

mangle of history, offering a realization of our own mortality.

Walter Benjamin, citing a 1896 text by Paul Lindau, observes that at a

certain point, the motif assumes the nature of social critique (Benjamin 2017,

1157). Perhaps, the latter also shows through Piasecki’s works with the doll motif,

on top of all sorts of existential and meta-psychological threads? Perhaps the

world, or more precisely Polish post-war and communist realities of the 1950s

and 1960s in which the artist happened to live were so gruesomely foreign that

the dolls had to be permanently imbued with soul and imagination, and raised

above objects in order to survive and leave a testimony to the complexities of

the human condition?

References

Benjamin, Walter (2017). Die Puppe, der Automat. In Walter Benjamin, Das Passagen-Werk (S. 1156- 1163). Musaicum Books / OK Publishing.

Didi-Huberman, Georges (1999). Was wir sehen, blickt uns an. Zur Metapsychologie des Bildes. München: Fink Verlag.

Freedberg, David (1989). The Power of Images. Studies in the History and Theory of Response. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Marzec, Andrzej (2015). Widmontologia. Teoria filozoficzna i praktyka artystyczna ponowoczesności. Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana.

Menninghaus, Winfried (2003). Disgust. Theory and History of a Strong Sensation. New York: State University of New York Press.

Rilke, Rainer Maria (1994). Dolls. On the Wax Dolls of Lotte Pritzel (translated by Idris Parry). In Classics Essays on Dolls. Heinrich von Kleist, Charles Baudelaire, Rainer Maria Rilke. London: Penguin.

Szyjkowska-Piotrowska, Anna (2015). Po-twarz. Przekraczanie wizualności w sztuce i fotografii, Gdańsk-Warszawa: Wydawnictwo słowo/obraz terytoria./p>

List of Figures

(The series of black-and-white photographs are from the 1950s and 1960s).)

Figure 1: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 12,9 x 15,9 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 2: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 15,9 x 12,9 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 3: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 14 x 18,5 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 4: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 17,6 x 11,8 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 5: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 17 x 24 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 6: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 42,5 x 31,5 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 7: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 21,6 x 16,6 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 8: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 24 x 17,8 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 9: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 24 x 17,8 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 10: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 12,9 x 15,9 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 11: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 12,9 x 15,9 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 12: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, mixed technique, 24 x 18 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 13: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 8,5 x 11,5 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 14: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 8,5 x 11,5 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Figure 15: Marek Piasecki, untitled, from the series Lalka / The Doll; black and white photograph, 10,2 x 13,2 cm; courtesy of the Gallery Piekary Poznań

Über die Autorin / About the author

Marta Smolińska

Prof. Dr. leitet den Lehrstuhl für Kunstgeschichte und Philosophie an der Universität der Künste Poznań (Polen). Kuratorin und Kunstkritikerin, Nomadin und Grenzgängerin. 2003 Promotion in Poznań („Młody Mehoffer” – „Der junge Mehoffer”). 2005–2006 und 2009 Stipendiatin der Stiftung für Polnische Wissenschaft. 2012 Stipendiatin des DAAD an der Humboldt Universität Berlin. 2013 Habilitation („Otwieranie obrazu. De(kon)strukacja uniwersalnych mechanizmów widzenia w nieprzedstawiającym malarstwie sztalugowym drugiej połowy XX wieku” – „Das Öffnen des Bildes. Die De(kon)struktion der universellen Mechanismen des Sehens in der ungegenständlichen Malerei in der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts“). 2014 Fellow an der Graduiertenschule für Ost- und Südosteuropastudien der LMU München. 2015 Stipendiatin der Stiftung Arp in Berlin. 2018 Stipendiatin des DAAD an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München und im Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in München. 2021 Stipendiatin des DAAD an der Freie Universität Berlin. Forschungen und Publikationen zu ungegenständlicher Malerei der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts, Border Art, Transmedialität und Haptik

Korrespondenz-Adresse / Correspondence address:

marta.smolinska@uap.edu.pl