denkste: puppe / just a bit of: doll | Bd.2 Nr.1 (2019) | Rubrik: Fokus

Puppen der Chancay-Kultur: Begleiter der Mumien

Isabel Martínez Armijo / Mercedes González / Anna-Maria Begerock

Focus: puppen als miniaturen – mehr als klein

Focus: dolls/puppets as miniatures – more than small

Abstract:

In pre-Columbian South America the custom of offering miniatures to the dead was

widespread. However, anthropomorphic textile dolls have only been found in the graves of one culture: Chancay. This culture flourished between 1200 and 1470 A. D. in large areas of what is today Peru's central coastal regions. The bodies of these small

dolls were made of plant fibers and then covered in textile clothing, which, together with

facial painting, distinguished gender. These dolls were often found holding objects.

Interestingly, although the dolls were always found with the buried mummy bundle, they

were not always alone, but often members of groups of dolls involved in activities such

as boat rides, dances or playing musical instruments thus representing daily activities or

special events from the life of the deceased.

Keywords: funerary dolls, Chancay culture, mummies, anthropomorphic figurines, grave goods, central coast Peru

Abstract:

In Südamerika war es in vorspanischer Zeit ein weit verbreiteter Brauch, den

Toten Miniaturen mitzugeben. Allerdings finden sich aus Textilien gefertigte

Puppen als Grabbeigaben nur in den Gräbern einer einzigen Kultur: Chancay. Die

Blütezeit dieser Kultur war zwischen 1200 und 1470 u. Z. Damals bestimmte sie weite

Teile der Zentralküste im Gebiet des heutigen Peru. Die Körper dieser kleinen Puppen

bestehen aus Pflanzenfasern, die mit Textilien bekleidet wurden. Sowohl anhand der

Kleidung als auch durch eine unterschiedliche Bemalung des Gesichts wurden die

Geschlechter voneinander unterschieden. Oft halten die gefundenen Püppchen bestimmte

Dinge wie Becher oder Musikinstrumente. Auch wenn diese Miniaturpuppen immer in

Beziehung zu einem Mumienbündel stehen, finden sie sich interessanterweise nicht

immer als einzelne Puppe, sondern oft auch in Gruppen, die gerade etwas zusammen

„unternehmen“: eine Bootsfahrt, Tänze oder auch das Spielen von Musikinstrumenten.

Alle diese Aktivitäten stellen Szenen aus dem Alltag oder auch besondere Ereignisse aus

dem Leben der Toten dar.

Schlagworte: Puppen; Chancay-Kultur; Mumien; Zentralküste Peru

Zitationsvorschlag: Armijo, I. M.; González, M.; Begerock, A.-M. Puppen Der Chancay-Kultur: Begleiter Der Mumien. de:do 2019, 2, 16-24. DOI: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:467-14632

Copyright: Isabel Martínez Armijo; Mercedes González; Anna-Maria Begerock. Dieses Werk steht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International.(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de).

DOI: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:467-14632

Veröffentlicht am: 02.09.2019

Um auf Zusatzmaterial zuzugreifen, besuchen Sie bitte die Artikelseite.

Introduction

In many Andean cultures of pre-Columbian South-America, from the Early Horizont (ca. 700 b.C-200 a.C) on with the well known Paracas culture in the central coast, the deceased were buried seated inside a burial bundle equipped with funerary objects that may have been of importance to the individual or were meant to be of assistance on the journey to the afterlife. Following the burial in rock niches or cemeteries at the coast, more offerings were added during rituals and on occasions to remember the dead. Some of the funerary goods in several burial contexts in the Andes are miniatures, small anthropomorphic or zoomorphic representations, imitations of daily life and ritualistic objects from these cultures. Since neither wheels nor carts were invented prior to the Spanish Conquest, all had to be carried on the back of either camelids or humans. Hence miniature offerings bore the pragmatic advantage of not adding much weight to the burial bundle. Certain other beliefs may have also been connected to them that are now lost due to the lack of writing in pre-Columbian times. However, the tradition of miniature offerings had been recorded for four thousand years in many different cultures along the South Coast of Peru, Chile and also for the Andean cultures in the highlands of Peru, Chile, and Bolivia culminating in high mountain offerings during the Incan times in shrines at extreme altitudes at the time of the Spanish Conquest, in the 16th century AD (Hoces de la Guardia, Brugnoli & Sinclaire 2006, 83f).

Among all types of miniature offerings, the textile ones were quite common and of great importance, reaching their maximum expression in three-dimensional figurines in the Chancay culture: the so-called “dolls”. The cemeteries of the Chancay culture can be found along the Central Coast of what is today Peru and are unfortunately, easily accessible and over the centuries have been heavily looted (Horkheimer 1963; Van Dalen 2012). Most of the burial contexts were destroyed and as a result important information is now lost. Despite the fact that only fragments of the various burial offerings of this culture are left, the most unique ones are the so-called Chancay dolls. These anthropomorphic miniature figurines have a vivid face with open eyes, making them a favorite object for public and private collections worldwide. Their popularity began with the early excavations of Chancay cemeteries in the late 19th and early 20th century and continue to be well sought after today either as lootings or modern copies. However, only a few studies exist on the original dolls themselves, the most abundant study from Hodnett (2004) and Gálvez (2017) on about 80 dolls from the Museo Amano collection in Lima, Peru. But almost nothing is known on how they were placed in situ and what messages they were meant to convey. This article offers various interpretations starting with a description of how these dolls were made, presenting what is known about their arrangement inside the burial as well as where they were found and finally outlining their meaning and modern impact.

Figure 1: Main archaeological Chancay sites on the Central coast of Peru

Chancay Culture

From 1000 to 1470 AD, a time period that is called the Late Intermediate Period (LIP), along the Coastline of what is today Peru, several local cultures developed and became independent from the dominating cultures of Huari and Tiahuanaco of the precedent period, the Middle Horizon. These local cultures dominated certain areas and as each of their emerging rulers tried to expand his territories, the influence of some grew over others. One of them was the archaeological culture known as Chancay that flourished between 1200 AD until 1470 AD along the Central Coast between the valleys of Huaura in the north to Chillón in the south (Young-Sánchez 1992, 45) (see figure 1). So far, large settlements have been found, one in Chancay, giving the culture its name, and one in Huaura (Gálvez 2017, 30). In that area and culture, people lived from agricultural subsistence production and fishing. A well-differentiated specialization in craftsmanship has been determined from the excavations. The Chancay culture displays an abundant iconographical repertoire on its ceramics, and in particular on its textiles. In pre-Columbian cultures in general, textiles played a predominant role, not only for dressing the living and equipping their environment, but also as an important gift to the dead. The deceased were wrapped in textiles, then placed into a burial bundle made out of textiles and then the bundle itself was covered in tunics and adorned with a false head, giving it the appearance of a human being (see figure 2). Since the production of the amounts of textiles needed was very labor intensive, they added to the value of the buried individual.

Figure 2: Drawing of a funerary bundle, showing the deceased in a squatted position inside it (Reiss & Stübel 1887: Plate 30)

In numerous graves, miniature textiles were also found as offerings. The techniques to produce these textiles and their ornaments changed within the various pre-Columbian cultures, but textiles and the iconography on them had always been used to convey ideas, memories, to define identity and therewith to act within religious, political and economic areas. The Chancay culture is well-known for its rich and varied textile production (Young-Sánchez 1992) including the handling of diverse textile techniques that allowed the weavers to capture a rich iconography with zoomorphic, anthropomorphic and supernatural beings. Likewise, through the use of such technological diversity, they created not only two-dimensional textiles, but also three-dimensional ones like the “Chancay dolls”. These small figurines are so captivating that they can be found in almost every pre-Columbian collection around the world and are always emblematic of the Chancay-culture. However, due to the lack of writing in pre-Columbian times and the insufficient documentation of the Spanish during their conquest, most of the information portrayed on textiles from pre-Columbian times is not yet deciphered and we are only beginning to understand their meaning. Further loss of information occurred during the excavations in the late 19th and early 20th century (see figure 3). These did not aim to document the contextualization of artifacts, but focused mainly on the quick extraction of objects from pre-Columbian graves, still a common practice of looting today. Hence for most dolls, their original placement on or around the mummy bundles is now lost.

Figure 3: The excavation methods of in the late 19th, early 20th century, when neither a detailed documentation of the findings nor contexts were considered important (Reiss & Stübel 1887: Plate 6)

Types of Funerary Dolls

The three-dimensional Chancay-dolls, always between 20 and 25 cm high, were entirely made with textile techniques. Reed (Typha angustifolia) and pieces of wood sewn together with cotton thread made up their internal structure. Larger reeds became arms and legs; for fingers and toes smaller reeds were added. This body-structure, either rigid or flexible, was then wrapped with yarn of a carmine or beige color to give the doll some skin, a technique simply called wrapping. The head is the most visible and prominent part of the doll as it occupies almost one third of the whole body. It shows two open and vivid eyes, a nose- generally in relief- and an open mouth showing teeth. The body of the doll was then covered with small textile clothing, especially woven for the purpose of dressing these dolls (Young-Sánchez 1992, 46; Hodnett 2004, 9; Hoces de la Guardia, Brugnoli & Sinclaire 2006, 84; Gálvez 2017, 92). Several kinds of these dolls have been identified and are available in collections. However, due to the fact that dating methods are expensive and the dolls are considered to be primarily of decorative value, most of them remain undated. Further, because a classification of the types was undertaken according to their formal appearance, information on coexistence or on the evolution of styles is unknown. The most representative type can be found in several museums and private collections both in Peru and around the world.1 Its main characteristic is the woven tapestry face with facial painting in various colors. Their position in reference to the bundle, on it directly or placed next to it, is completely unknown. A second type shows faces on brown simple fabric with embroidered or painted eyes and mouth (Lothrop & Mahler 1957, Plate XVII; Gálvez 2017, 82). In two cases, this second type was directly associated with the burial bundle, as shown in one bundle in the Museum of Natural History of Washington, and another one in the Ethnologisches Museum of Berlin. A third type of these dolls has a wrapped face, usually of red wool, with embroidered eyes and mouth. One example can be found at the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino of Santiago (see Hoces de la Guardia et al. 2006), and several at the Canadian Museum of History (see Beheshteh 2015). A fourth type of doll has the face in plain weave and the eyes, mouth and nose embroidered. But unlike the other types, the clothing on the dolls of this type seem not to have been made to measure, but were merely made of reused fragments of ancient fabrics that were wrapped around their bodies - very similar to the dolls that are manufactured and sold today in the artisan markets in Peru. Some of these specimens are found at the Canadian Museum of History and the Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez (FANJ) in Cuba (see figure 4).

Figure 5: Female Chancay doll carrying a babyFigure 5 (FANJ, Havana, Cuba)

Figure 4: Chancay funerary bundle in the Ethnologisches Museum of Berlin

The largest sample, of around 80 Chancay dolls in one collection, can be found in the Amano Museum in Lima, Peru. They all belong to the first, most elaborate type (see figure 5). These figurines deserve closer examination as they have prominent facial painting, are well-differentiated as male or female and wear a reproduction at scale of the Chancay clothing according to their gender.

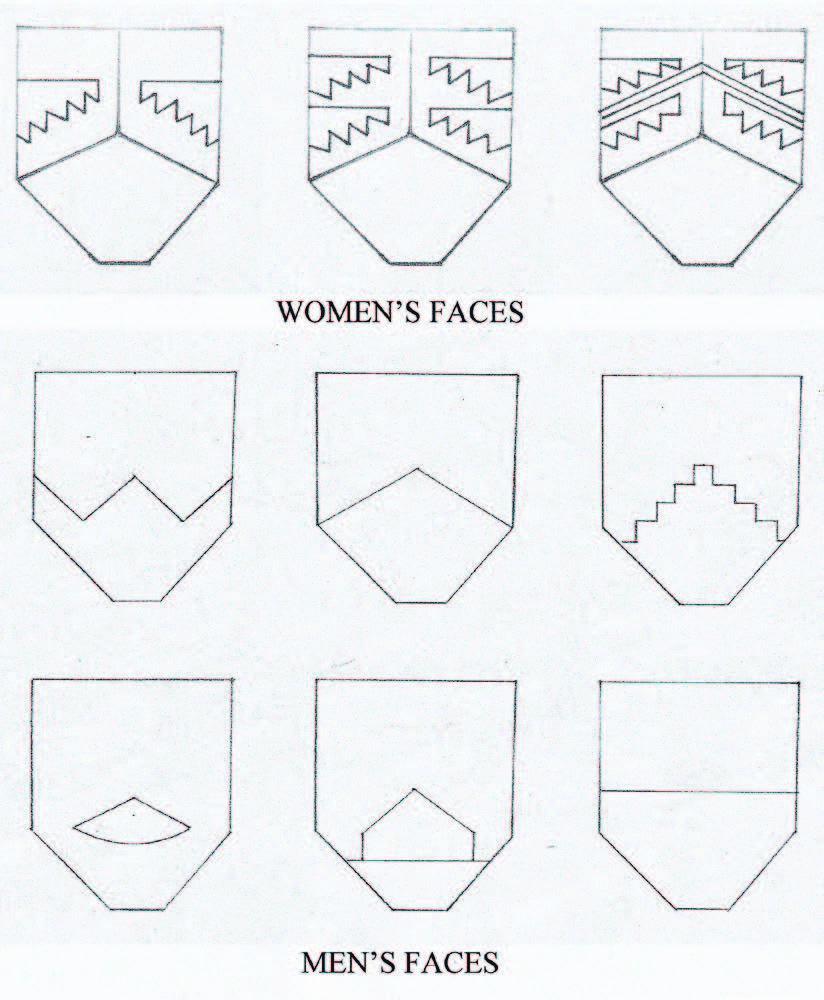

Face/facial patterns

The face either of irregular pentagonal, trapezoidal or semicircular shape, was made using a slit tapestry technique2 with cotton warp and camelid wool weft woven only in its front part and tied or stitched on the back by the warp surplus (Stone- Miller 1992, Hodnett 2004, Gálvez 2017). Several colors were used to make up the face divided in three sections for the female and two sections for the male dolls. Female dolls have more complex facial patterns with two upper sections of different colors with the nose serving as a dividing axis and one lower section. The upper sections are often in ochre and carmine with each section being around one eye. Elaborate representations of facial decorations like geometric stepped motifs were also created, reflecting mirror-like on each side of the face but with an inversion of the colours. The lower section is always a bright pink or beige. Here the mouth is found with black and white teeth. The males´ faces show simpler facial patterns with one upper section in plain color in rosy red and the lower one in yellow.3 Small variations in design can be observed, but they are always shown without pattern (see figure 6).The eyes were also already woven into these textiles, with white and black thread, showing them as open and vivid. The same applies to their mouths, also being woven and shown as open and with teeth. Noses were made by tapestry or needle-knitting with red yarn onto the faces, making them three-dimensional (Hodnett 2004, Gálvez 2017). This shows that the dolls were perceived as animated beings able to breathe, speak, eat and live.

Figure 6: Female Chancay doll with the typical tapestry face (www.ancientorigins. es; public domain)

Wig/headdress

Male and female dolls received shoulder-long loose hair made out of thick threads of camelid fibre in black or dark brown. Here too a differentiation between the sexes was made by the headwear. Some female dolls wear a gaze-cloth on top of their hair in different sizes and making while others wear a headband made by several turns of yarn around the head. This headband can be found on male dolls as well, though here it is sometimes a small woven cloth strip. Interestingly, all these types of head ornaments have been found on mummies from that time and culture as well, showing again, that these dolls imitate the living (Hodnett 1999, 16; Hoces de la Guardia et al. 2006, 84; Gálvez 2017, 86ff., Reiss & Stübel 1887: Plate 30).

Clothing

Sex differentiation was also indicated by the dolls' clothing: female dolls wear a long dress, a quadrangular fabric reaching down to the ankles with two openings for the arms and one for the head. The spatial composition can be in horizontal strips of different colors made with the tapestry technique or covered by concentric diamonds (Gálvez 2017) in two contrasting colors made with the twill technique. Additionally, in some cases, these dolls wear a gauze cloth over their shoulders. Male clothing consists of a short tunic or uncu and a loincloth or wara which vary in terms of decoration and colour range (see Hodnett 2004 and Gálvez 2017). As aforementioned, the woven patterns on pre-Columbian textiles show the cosmological beliefs of the people. Landscapes, social structures, and religious realms, as well as animals, interlock in the display and are all mostly deciphered. Therefore, it can also be assumed that the clothing of these dolls conveyed messages of importance to the people offering these dolls to the dead and thus transferred to the deceased. This is especially important since all textiles appear to have been made especially for the dolls. Specialized workshops that only produced miniature textiles for the offering to the deceased and to dress these dolls may have existed as discussed by Hodnett (2004), Hoces de la Guardia et al. (2006) and Gálvez (2017). However, no such workshop has been found to date.Further adornments were mostly added to female dolls such as necklaces and wristbands. In their hands these dolls hold various objects such as cotton cones, gauze cloths, fringes, ribbons (Gálvez 2017, 89). Further, they are shown in activity: female dolls holding mini-looms and male dolls holding wind or percussion instruments or containers and slings (Hodnett 2004, Gálvez 2017). The Chancay weavers also created other beings of the animal and vegetal realms such as camelids, birds and trees (Hoces de la Guardia et al. 2006, 82f; Bussagli, Thomas, Pommier & Mainguy 1987, 251), placing the dolls into a scenery.

Companions of the mummies: meaning/interpretation

As reproductions to scale of anthropomorphic beings, these three-dimensional figurines received the modern denomination of “doll”, but we actually lack their original name and interpretation. As aforementioned, they can be found in almost every private and public textile collection in Latin America, North America, and Europe, and probably in even more areas around the world although only very few were documented in situ before being excavated and brought to these collections. It cannot be determined whether any of these dolls were placed in the grave at the time of the burial, or as secondary offerings in later rituals due to the poor documentation and heavy looting of pre-Columbian burial sites in South America, which lead- and still leads- to a decontextualization of burials and their associated artifacts. Despite the rarity of in situ dolls, two bundles were found for this study, one in the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. and the other in the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin, Germany. Here, a thin rod was pushed through the doll and then through the outer textiles of the bundle in order to attach the doll (Gálvez 2017, 81). In both cases it seems quite likely that this is one option for the original placement of individual dolls. One interpretation perceives dolls as substitutes4 resembling lost children or children that the deceased may have wished for.

Figure 7: Types of Chancay doll’s faces identified by Hodnett (1999)

The positioning of the Chancay dolls shows them undertaking a variety of activities. Some hold a cup and may be offering it or enjoying a drink themselves (Stone-Miller 1992, 156; Hodnett 2004, 8) while others play instruments (Hodnett 2004, 17). Only seldomly are the dolls alone. Some of them were placed either next to each other and seem to be dancing (ibid., 12), or even on top of each other and seem to be performing acrobatics (ibid., 17). Others were sewn onto small stuffed pillows in pairs or in a group. The “surroundings” were also created out of woven textiles, like a tree around which a group of several male dolls seems to be dancing (Bussagli et al. 1987, 13; Hodnett 2004, 19; Beheshteh 2015, 18) or a house with the dolls placed inside peeking out (Hodnett 2004, 20f.)5 or others riding in a boat (Beheshteh 2015, 86) (see figure 7). These dolls, arranged in groups, served as an external offering to the deceased person inside the mummy bundle (Young-Sánchez, 46). Thus, the dead person was not alone, but accompanied by a group en miniature with a certain task to fulfill. Pre- Columbian cultures shared the belief that the deceased would continue to live either in a distant world or as a new, and most importantly, vivid being. The mummy bundles with false heads often show faces with open eyes, an open mouth and a nose, giving the new form of the deceased placed into such a bundle a new but animated form as the dolls are shown as vivid beings. Furthermore, it was a custom to take care of the deceased by visiting them frequently during festivities and rituals on which occasions they were offered food and items as well as to repair broken bundles (Begerock 2016, 272, 407). Secondary offerings were brought along on these visits. Such dolls may have been viewed as messengers from the living to the dead. The activities shown by the arrangement of the dolls led the researchers to various interpretations: perhaps these rituals portrayed rites de passage, important occasions of the individual's life, or events that the burying community wished for the deceased person in the other life, or those to be remembered, thus making the dolls mementos. It is also noteworthy to mention the distinction in the types of Chancay burials, both in the layout of the graves and in the quality and quantity of funeral offerings, which indicate a differentiation of status between the common population and the elite. Important to note is that the objects included in the burial only represent parts of the deceased's belongings chosen and placed into the grave by the living community left behind. Thus, these burial offerings may only partially represent the wishes of the deceased, but more the ones of the burying community reflecting their traditions and decisions on what is appropriate or necessary for that deceased person in the afterlife. Unfortunately, and this applies to both the first and second type of doll arrangements, a connection between the dolls, their sex, their number and the activities they are involved in and the deceased person in the bundle cannot yet be made. So far they do not seem to be gender-related offerings, nor toys6 - by the fact that they were found in adult graves (Beheshteh 2015, 17). It remains unclear if these dolls were perceived as servants. An example of buried human servants with their lord is found for the Moche-culture from the North coast of what is today Peru, (600 BC to 600 AD). Here it is known that servants and wives or concubines kept the dead male ruler, e.g. the Lord of Sipán, company. These servants were buried with him; one even placed into a corner arranged as if watching over the dead. This servant is also missing one foot and therefore hindered from running away from his task. It cannot be confirmed whether or not the dolls of the later Chancay culture were regarded as servants or as performers of certain rituals necessary for the deceased. However, their presence in Chancay burials is so prominent that whenever they are found it is clear that they stem from burial contexts of that very Chancay culture. Some Peruvian archaeologists go even further and interpret these dolls as having a kind of magical character related to the Chancay worldview (Kauffmann Doig 1978, 512). The colored faces may represent a significant link to death and afterlife due to the fact that yellow and red were used in pre-Columbian cultures related to the feminine and masculine as well as elite and magical power (Bárcena 2001). When the Chancay culture disappeared, the Incas expanded their territory and took over the power in administrative and religious terms. Their most known ritual was the sacrifice of children on high mountain peaks. Interestingly, they also offered small anthropomorphic figurines on those high mountain shrines, dolls made of silver, gold, or Spondylus (a sea shell) that were dressed in miniature clothing. This would have been the culmination of this long Andean tradition of production and offerings of miniatures. On many occasions these Inca figurines accompanied children and young women sacrificed on the mountain peaks, but they can also be found as singular offerings. Again the interpretation of these miniature figurines varies, from representations of the Inca deities and the high mountains (Reinhard & Ceruti 2010), to representations of the different panacas (lineages) or members of the Inca nobility (Martínez 2006 and 2007) or even as symbols of the Incas groups responsible for the control of newly conquered areas (Mignone 2015). Following these interpretations of the later Inca miniature figurines, we could add possible interpretations to the Chancay dolls, namely that they were made especially as funeral offerings, perhaps as representations of some relatives of the deceased as a special "sacrifice" or replacement. They were created as vivid figurines, supposed to accompany the deceased into another life, to care for him, to celebrate with him, to “live” with him.

Figure 8: Chancay dolls riding a boat (FANJ, Havana, Cuba)

Modern copies? And modern copies!

Dating pre-Columbian artifacts costs money most institutions inside and outside Peru either do not have or do not wish to invest in such small artifacts as the Chancay dolls. Therefore, archaeological dating is a less cost intensive way to determine whether an artifact is modern or old. Interestingly enough, a difference in the technique of creating the face of the Chancay dolls serves as such a dating method. This method is even used by American customs as stated in the US Import Restriction List, Federal Register Notice, updated on the 06/07/2017: “Dolls – Three dimensional human figures stuffed with vegetal fiber to which hair and other decorations are added. Sometimes they depict lone females; in other cases they are arranged in groups. Most important, the eyes are woven in tapestry technique; in fakes, they have embroidered features. Usually 20 cm tall and 8 cm wide”.7 This lists items subject to the US regulation against the import of Peruvian Antique artifacts implicitly showing that traffic of modern reproductions of these dolls is not prohibited. Certainly these modern reproductions provide important financial contributions to uncountable very poor households in modern Peru. Due to political struggles and a generally very dry climate, many suburban or rural communities in Peru suffer from poverty. Around their settlements are the pre-Columbian cemeteries that have been intensively excavated or looted for at least 250 years. Excavators and looters left “uninteresting” items like textile scraps and mummy parts behind. The textiles are nowadays recycled and used for the modern production of Chancay dolls – a unique, recognizable, cheap and small-enough-to-carry tourist souvenir reminiscent of Peru´s past. These dolls are made with less effort than the original Chancay ones. They do not portray scenes anymore when arranged in groups. The clothing is sewn together from scraps of ancient textiles; they are recycled and not woven for the dolls explicitly. The faces are embroidered and again made from textile scraps, that have been recycled but not been woven for the dolls. Furthermore, most of the dolls are female (see figure 8). In order to increase their price at the Peruvian markets, sometimes “caldo de momia” (mummy soup) is made. Here, a hole is dug into the ground and all recently made pottery in the old style as well as the modern Chancay dolls are placed inside. On top of the opening of that underground chamber, a pre-Columbian mummy or leftovers of a mummy are burned, thus giving the newly created artifacts an old smell making them apparently older and thus increasing their retail price. Besides the very basic need to create income, a growing number of artists and weavers in Peru are interested in continuing this rich tradition by making recreations of the dolls with the tapestry face to represent the facial painting (see figure 9).

Figure 9: Modern Chancay dolls from a Cusco craft market)

Conclusion

The colorful Chancay dolls have so far only been identified as funerary objects and not as objects used in other contexts as, for example, in the household. Their vivid faces and arrangement in burials as well as their positioning in groups involved in activities has resulted in the interpretation that these dolls served as accompaniment of the deceased. It remains to be determined if they were seen as servants, performers of rituals, or as mementos. Unfortunately, only few studies have focused on a detailed analysis of these dolls and dating methods were rarely applied. Since the Chancay culture existed for nearly two centuries, changes in style and technique are most likely. It is most probable that the corpus of the scenes of these dolls was amplified, but the quality of the dolls reduced. Regional variations also have to be considered, but are not yet determined. Whenever the Chancay culture is considered, their textile dolls are mentioned as the most prominent feature, distinguishing this pre-Columbian culture from all others. These dolls have such a characteristic appearance that wherever they are displayed they can always be identified as belonging to the Chancay-culture. Hence, the study of the Chancay dolls, their making and their meaning remains a field to be investigated further. This study is intended to present the different types and interpretations of these dolls as an important part of the Peruvian heritage. Modern copies of the Chancay dolls not only add income to poorer households, they also bring growing attention to this long and rich Andean textile tradition.

[1] Amano Museum in Lima, Peru (see Hodnett 2004 and Gálvez 2017). Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, in Santiago of Chile (see Hoces de la Guardia et al. 2006), Museo Larco, Lima, Peru (http://www.museolarco.org/ catalogo/ficha.php?id=14804, access November 20, 2018), Museum of Fine Arts of Boston (see Stone- Miller 1992) and Birmingham Museum (https://www.flickr.com/photos/birminghammag/6045093855/, access November 20, 2018), among others.

[2] In this technique, known as kilim too, the discontinuous wefts are not linked together by several successive passes, causing a shorts opening in the vertical direction (Hoces de la Guardia et al. 2006, 97).

[3] For more details on the different types of facial paint in female and male figurines, see Hodnett (2004) and Gálvez (2017).

[4] For a discussion on pre-Columbian statuettes and dolls see Schuler-Schömig (1984).

[5] The references available regarding the findings of these miniatures associated with funerary bales indicate the following architectural Chancay centres: Pisquillo Chico, Pisquillo Grande, Caqui, Lauri, Pampa Hermosa, Cerro Trinidad, Macas, Matucana and Palpa (Hodnett 2004, Gálvez 2017).

[6] For a discussion on the interpretation of pre-Columbian artefacts as toys or sacred objects see Thiemer- Sachse (2002).

[7] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/06/07/2017-11841/extension-of-import-restrictionsimposed- on-archaeological-and-ethnological-materials-from-peru, access November 20, 2018

Literature

Bárcena, Roberto (2001). Pigmentos en el ritual funerario de la momia del cerro Aconcagua. In JuanSchobinger (Ed.), El santuario incaico del cerro Aconcagua (pp. 117-170). Mendoza: Universidad Nacional de Cuyo.

Begerock, Anna-Maria (2016). „Ein Leben mit den Ahnen - Der Tod als Inszenierung für die Lebenden. Eine Untersuchung anhand ausgewählter Kulturen des westlichen Südamerika zu Hinweisen einer intentionellen Mumifizierung der Verstorbenen und der kulturimmanenten Gründe“. Doctoral thesis. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

Beheshteh, Asil (2015). Chancay Style Textiles in the Canadian Museum of History. Thesis for Master of Arts. Ontario: University of Western Ontario.

Bussagli, Mario, Thomas, Michel, Pommier, Sophie, Mainguy, Christine (1987). Arte del tessere. Roma: Editalia.

Gálvez, Meissie (2017). Pintura facial, patrón de vestido y cabellos en las miniaturas textiles de la cultura Chancay. Thesis for Master in Peruvian and Latinoamerican Art. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

Hoces de la Guardia, Soledad, Brugnoli, Paulina, Sinclaire, Carole (2006). Awakhuni. Tejiendo la Historia Andina. Santiago: Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino.

Hodnett, M.K. (2004). Pre-Columbian Dolls in the Amano Museum. Muñecos Precolombinos en el Museo Amano. Lima: Fundación Museo Amano.

Horkheimer, Hans (1963). Chancay prehispánico: diversidad y belleza. Cultura Peruana 62-69, 175-178.

Kauffmann Doig, Federico (1978). Manual de Arqueología Peruana. Lima: Iberia S.A.

Lothrop, Samuel Kirkland, Mahler, Joy (1957). A Chancay-Style Grave at Zapallan, Peru. An Analysis of its textiles, Pottery and other Furnishings. Paper of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University L (1).

Martínez, Isabel (2006). Vestimenta de las estatuillas antropomorfas incas en el contexto de la capacocha: un estudio preliminar. Actas XXVIII Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, 231-237.

Martínez, Isabel (2007). Acsu, llicllas y panacas: la vestimenta de las ofrendas antropomorfas incas como símbolo de poder. Actas IV Jornadas Internacionales sobre Textiles Precolombinos, 535-549.

Mignone, Pablo (2015). Illas y allicac. La capacocha del Llullaillaco y los mecanismos de ascenso social de los “inkas de privilegio”. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 20 (2), 69-87.

Reinhard, Johan, Ceruti María Constanza (2010). Inca Rituals and Sacred Mountains: A Study of the World’s Highest Archaeological Sites. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeological Press, University of California.

Reiss, Wilhelm, Stübel, Alphons (1880-1887). The Necropolis of Ancon in Peru: a contribution to our knowledge of the culture and industries of the empire of the incas, being the results of excavations made on the spot by W. Reiss and A. Stübel. Berlin: A. Asher & Co.

Schuler-Schömig, Immina von (1984). Puppen oder Substitute? Gedanken zur Bedeutung einer Gruppe von Grabbeigaben aus Peru. Tribus 33, 155-168.

Stone-Miller, Rebecca (Ed.) (1992). To Weave for the Sun. Ancient Andean Textiles in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. London: Thames and Hudson.

Thiemer-Sachse, Ursula (2002). Spielzeug oder sakrales bzw. rituelles Objekt? Ethnologisch-Archäologische Zeitschrift 43, 93-115.

Van Dalen Luna, Pieter (2012). Contextos funerarios chancay en Macatón, Valle de Chancay-Huaral. Arqueología y Sociedad 25, 259-302.

Young-Sánchez, Margaret (1992). Textile Traditions of the Late Intermediate Period. In Rebecca Stone-Miller (Ed.), To Weave for the Sun. Ancient Andean Textiles (pp. 43-49). London: Thames and Hudson.

List of figures

Figure 1: Main archaeological Chancay sites on the Central coast of Peru

Figure 2: Drawing of a funerary bundle, showing the deceased in a squatted position inside it (Reiss & Stübel 1887: Plate 30)

Figure 3: The excavation methods of in the late 19th, early 20th century, when neither a detailed documentation of the findings nor contexts were considered important (Reiss & Stübel 1887: Plate 6)

Figure 4: Chancay funerary bundle in the Ethnologisches Museum of Berlin

Figure 5: Female Chancay doll carrying a baby (FANJ, Havana, Cuba)

Figure 6: Female Chancay doll with the typical tapestry face (www.ancient-origins.es; public domain)

Figure 7: Types of Chancay doll’s faces identified by Hodnett (1999)

Figure 8: Chancay dolls riding a boat (FANJ, Havana, Cuba)

Figure 9: Modern Chancay dolls from a Cusco craft market

About the Authors / Über die Autorinnen

Isabel Martínez ArmijoIsabel Martínez studied archaeology at the Universidad Nacional San Antonio Abad in Cusco, Peru. She specialized in the study of pre-Columbian textiles and applies this knowledge to various related projects, investigations and workshops. Also, she worked as a forensic archaeologist, first in the Human Rights Program and then in the Special Forensic Identification Unit of the Legal Medical Service of Santiago, Chile, where she developed a methodology for analysing associated evidence in Human and Criminal cases. She is currently head of the Department of Archaeological Textile Analysis at the Institute for the Scientific Studies of Mummies (IECIM), Madrid, Spain, with textile projects in Europa and Cuba.

Korrespondenz-Adresse / correspondence address:

imartinez.iecim@gmail.com

Mercedes González

Mercedes González is the founder and President of the Institute for the Scientific Studies of Mummies (IECIM) in Madrid, Spain, and she is a senior anatomical pathology technician with specialization in necropsies. She was involved in the excavations of the Spanish writer Miguel Cervantes and is currently working in many mummy projects in Europe and Latin America. She is also the Scientific Director of the Museum of the Mummies from Quinto (Zaragoza, Spain), the first museum of mummies in Spain.

Korrespondenz-Adresse / correspondence address:

mgonzalez.iecim@gmail.com

Anna-Maria Begerock

Anna-Maria Begerock, Dr. phil., studied Latin American Archaeology at the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany and worked in several mummy projects in Europe. She is currently the head of the Andean Archaeology Department at the Institute for the Scientific Studies of Mummies (IECIM), Madrid, Spain, with mummy projects in Europe and Cuba, where she investigates the cultural origin of the mummies, their individual life – and acquisition history.

Korrespondenz-Adresse / correspondence address:

abegerock.iecim@gmail.com