denkste: puppe / just a bit of: doll | Bd.2 Nr.1 (2019) | Rubrik: Fokus

Ein Spiegel ihrer Zeit: Die Nussschalen-Studien über ungeklärte Todesfälle als Mikrokosmen Amerikas in der Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts

Courtney Leigh Harris

Focus: puppen als miniaturen – mehr als klein

Focus: dolls/puppets as miniatures – more than small

Abstract:

In the 1940s and 1950s, Chicago heiress Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962) created a

group of miniature rooms and buildings as tools for forensic investigators-in-training at Harvard Medical School’s Department of Legal Medicine. Known collectively

as the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, each represents a tiny, highly detailed crime

scene, for which Lee also created an accompanying text with additional information:

witness statements, weather reports, etc. It was Lee’s intention that the

Nutshell Studies would provide capsule crime scenes “at the most effective moment, very much as if a

motion picture were stopped at such a point” (Lee n.d.). This paper will explore Lee’s

literary work – both in her youth and in her accompanying texts for the

Nutshells. It will also look at the ways in which the themes of the

Nutshells’ crimes, carefully chosen

by Lee to represent issues relevant to her own day in the 1940s, are reflected in larger

cultural currents in American society. This reflection of contemporary social issues finds

strong parallels with crime film of the late 1940s and 1950s, particularly work of Alfred

Hitchcock. In turn, many anxieties of mid-century America are also reflected in the post-

9/11 world with an increased unease about terrorism, global migration, and globalism.

By understanding Lee`s and Hitchcock’s earlier work, we can better understand the 21st century’s attitude to similar concerns.

Keywords: Frances Glessner Lee, Alfred Hitchcock, miniatures, forensic science

Abstract:

In den 1940er und 1950er Jahren schuf die Chicagoer Erbin Frances Glessner Lee

eine Anzahl von Miniaturräumen und -gebäuden als Unterrichtsmaterial in der

Ausbildung von forensischen Ermittlern an der rechtsmedizinischen Abteilung der

Medizinischen Fakultät der Harvard Universität. Gemeinhin bekannt als die Nutshell

Studies of Unexplained Death („Nussschalen-Studien über ungeklärte Todesfälle“) stellt

jede Miniatur einen winzigen, aber höchst detailreich ausgestalteten Tatort dar, für den

Lee zudem jeweils einen Begleittext mit ergänzender Information erstellt hat: Zeugenaussagen,

Wetterberichte usw. Es war Lees Absicht, mit den Nutshell Sudies Tatortszenen zur

Verfügung zu stellen, die – wie eingekapselt – „exakt den richtigen Moment treffen, so als

ob ein Film genau an dieser Stelle angehalten wird“ (Lee o. J.). Der vorliegende Beitrag

untersucht Lees Schriften – sowohl die aus ihren jungen Jahren als auch die Begleittexte

zu den Nutshells. Betrachtet wird zudem, in welcher Weise die Themen der Nutshells-

Kriminalfälle, die von Lee damals sorgfältig unter dem Aspekt der für ihre Zeit der

1940er Jahre relevanten sozialen Fragen ausgewählt wurden, auch größere kulturelle

Strömungen der amerikanischen Gesellschaft widerspiegeln. Die Einbeziehung dieser

zeitgenössischen sozialen Themen findet deutliche Parallelen im Kriminalfilm der

späten 1940er und 1950er Jahre, insbesondere in den Werken von Alfred Hitchcock. Viele

der Ängste im Amerika der 1950 Jahre spiegeln sich angesichts der wachsenden

Beunruhigung über Terrorismus, weltweite Migration und Globalisierung auch in der

Welt nach dem 11. September wider. Versteht man die zeitlich früheren Arbeiten von

Lee und Hitchcock, lässt sich die Einstellung im 21. Jahrhunderts gegenüber ähnlichen

Themen besser nachvollziehen.

Schlagworte: Frances Glessner Lee; Alfred Hitchcock; Miniaturen; Forensi

Zitationsvorschlag: Harris, C. L. Ein Spiegel Ihrer Zeit: Die Nussschalen-Studien über ungeklärte Todesfälle Als Mikrokosmen Amerikas in Der Mitte Des 20. Jahrhunderts. de:do 2019, 2, 34-42. DOI: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:467-14632

Copyright: Courtney Leigh Harris. Dieses Werk steht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons Namensnennung - Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International.(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de).

DOI: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:467-14632

Veröffentlicht am: 02.09.2019

Um auf Zusatzmaterial zuzugreifen, besuchen Sie bitte die Artikelseite.

Introduction and background1

To explore the unusual and intriguing quality of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, one must first understand fully their unique creator. To contextualize her background and upbringing, this article will begin with a short biographical sketch of Frances Glessner Lee. Lee was born into a wealthy Chicago family in 1878. Her father, John Jacob Glessner, was a principal in a company that made farm equipment. When Frances was young, John Glessner commissioned Boston architect H. H. Richardson to build him a house on Chicago’s south side. That house, today known as the Glessner House, is Richardson’s residential masterpiece. It was unusual for its day: it featured a heavy, almost fortified façade with limited windows, and none of the era’s typically gendered spaces (e.g. a study for the men, a drawing room for the women). John and his wife, also named Frances, worked together at a large partners desk in the library.2 Lee’s childhood home featured minimal windows on the exterior, but many windows on the portion looking out onto an interior courtyard. It was an unusual house for its day, and growing up there may have shaped Lee’s perspectives on the nature of the home and neighborhoods. Now a museum, the house is an architectural masterpiece and, as such, is well documented. Glessner Lee’s own father wrote a book about the house; it makes clear that her childhood must have been unusual, with permeable borders (Glessner 2011). Lee’s mother, who hosted a weekly reading class, welcomed over 80 people each session. This eroding of the private space – rendering it public – obviously had an impact on the younger Frances’s later work (Miller 2005, 204). The majority of Lee’s later work, the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death feature some sort of similar erosion, whether it is of a neighbor peeking in, or an unexpected visitor. The domestic space of the home was not impenetrable, and indeed, was permeable. Thus, Lee grew up in the late 19th century in an upper-class house where books played a major role. In the Monday Morning Reading Classes, hosted by her mother Frances Glessner, women would attend and listen to a professional reader for an hour, before engaging in discussion. The reading group likely did not indulge in some of the more ‘popular’ literature of the day, but Lee herself surely knew of the works of Edgar Allen Poe, who wrote some of the first works that can be considered ‘detective stories’. She likely also knew the work of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, featuring his famous detective, Sherlock Holmes. As a child, she wrote imaginative short stories and lyric poems, creating involved characters, scenarios and worlds.3 In her later work on the Nutshells, this creative and literary impulse served her well. Furthermore, Lee’s mother was also a keen silversmith and jeweler. Her jewelry, made at a workbench at home, was in the Arts & Crafts style, mirroring much of the furniture of the house itself. This focus on hand-craft in the home from an early age may have influenced Glessner Lee’s decision to turn to model- making. As has been pointed out by others, miniature objects are innately linked to a pre-industrial labor and a nostalgia for craft because of the need to hand make them (Stewart 1993, 68).

Founded only 45 years before Frances’ birth, Chicago was a city which had rapidly developed into a major hub in the middle of the United States. John and Frances Glessner had relocated from Ohio, part of a wave of new arrivals in the city in the mid-19th century. Indeed, the new prestige and wealth of Chicago was demonstrated when in 1890 Congress awarded the city the right to mount the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893.4 The Glessners, like many of their fellow Chicagoans, visited the fair many times, even choosing not to spend the summer at their estate on the East Coast to be able to make the most of the fair’s short run. The younger Frances was educated at home with her older brother, George, who was a delicate child, frequently suffering from ill health. At the family doctor’s suggestion, the Glessners spent summers away from Chicago on a large estate in New Hampshire called The Rocks. George was educated at Harvard, where he was a classmate of George Burgess Magrath, who would become medical examiner for the southern region of Suffolk County, in Massachusetts, in 1907. Dr. Magrath later served as a critical influence in Frances’ life, helping to introduce her to the field of medical examination. Frances married the lawyer Bewett Lee at the age of 19 and had three children, though she and her husband divorced in 1914. Years later, in 1938, she settled permanently at the family property in New Hampshire, spending all of her time in New England. Traveling south to Boston, she had the opportunity to work with Dr. Magrath, through whom her interest in police investigation, medical examination and the burgeoning field of forensic science grew (Jentzen 2009, 40ff.). In the 1940s, most city or county coroners were political appointees, rather than trained professionals. In time, Lee developed a desire to make the field of crime scene investigation more professional. Following her father’s death in 1936, she had inherited a large portion of his estate and thus the means by which to support the cause: she provided $250,000 to Harvard University in 1936 to establish a Chair in Legal Medicine, with the full department dedicated to the field established in 1937.

The ‘Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death

Frances Glessner Lee recognized that without continual access to crime scenes – hardly a realistic possibility – Harvard’s Department of Legal Medicine could not adequately train police investigators in the art of crime scene investigation. Between the early 1940s and early 1950s, she set out to create miniature dioramas of crime scenes – some imagined, some composites of actual crimes – to serve as training tools for would-be investigators, the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Each study is a masterpiece of intense creativity and features a physical diorama of the crime scene, as well as Lee’s own written statement and analysis. All eighteen of the surviving Harvard Medical School Nutshells feature at least one dead body, with one diorama featuring three deceased figures. In some cases, the cause of death is suicide, in some murder; in some, the death is accidental, and in some the cause remains (intentionally?) unknown. The statements provide critical witness statements, background information, details about time of day, temperature, etc., that the investigator might use to uncover what had happened. As Lee instructed her students, their goal was to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell” (Lee n.d.). Together with the Department of Legal Medicine, Lee hoped that her Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death would change the field of forensic science.

Figure 1: Parker Glass examining “Three Room Dwelling” Nutshell Study, taken 1961; Courtesy Glessner House

The Nutshells are not simply shrunken down ‘real’ crime scenes. Lee carefully crafted each Nutshell to convey a specific lesson, such as not to follow red herrings, to examine all physical evidence carefully, not to jump to conclusions. In the spirit of other instruction objects, such as the Harvard University’s Blaschka Glass Models of Plants5, the Nutshells, in their smallness, are more perfect than full-size crime scenes. Flowers and natural specimens, like crime scenes, are fleeting and hard to capture (Rossi-Wilcox 2015, 200). By creating ‘models’ – in the case of the glass flowers, full-size, and in the case of the Nutshells, miniature ones – their creators were ‘fixing’ them in a more permanent way, enabling entire fields of study to advance as never before. Lee hosted a yearly seminar, called the Harvard Associates of Police Science, where police officers could attend and learn new forensic science techniques and study with her Nutshells. Many attendees were local to New England, but some attended from as far away as the United Kingdom. Attendees were paired up, given a flashlight to examine the crime scene in detail and had 90 minutes to investigate two studies (see figure 1). They would then report their findings to the larger group. The Nutshells offered many didactic opportunities, including: collaboration, close-looking and observation, note-taking, and critical thinking. Such educational focuses would not have been out of place in scientific classrooms at American universities in the 1940s and 1950s.

The Harvard Medical School’s Department of Legal Medicine closed its doors in 1967, following Lee’s death in 1962. At that time, the Nutshells were placed on long-term deposit at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore. Today, they continue to be used actively for two training sessions per year by the successor to Lee’s seminar: Harvard Associates in Police Science (HARP), where Lee’s own methods are still embraced. Due to their continued use, the analyses and ‘solutions’ for the Nutshells are not made public, aside from a few select instances (Botz 2004, 220). A selection of the surviving Nutshells were featured in an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where they were explored from a craft perspective and exhibited to a wide audience for the first time.6 In darkened galleries, visitors were encouraged to use flashlights and to consider investigative methods and critical thinking, just as HARP attendees still do today.7 While not on a miniature scale, many medical and nursing schools today have ‘simulation’ centers where students act out scenarios, responding to scenarios and animated mannequins.8

Frances Glessner Lee’s creativity

Within each model, Lee carefully selected specific details: nothing is included – or left out – by chance. She was careful to include only as much information as the investigator needed to uncover the truth. In addition to the visual evidence before the investigator, the written statements that Lee provided for each of the characters in her models is intensely literary. Motives, emotions, relationships – all are present, making each Nutshell seem like its own world, inhabited by real people. As a young child, Lee began writing short stories, starting in 1894 when she was sixteen years old. One particularly telling story, ‘The Mysterious Disappearance of Giovanni Seiaglia’, recounts a story featuring a narrator named ‘Francesca Kent’ who meets a young man while she is traveling in Italy with her parents. The story includes elements of Lee’s own life—not least of which the main character’s name, upper-class lifestyle, and the summer house called the ‘Rocks’, but it cleverly deviates away from reality, featuring a dramatic scene where in an argument, Giovanni grabs a knife and threatens to end both of their lives. Shortly after, he was summoned away with a telegram and did not return. She attempts, in vain, to find him, but he had disappeared. The short story concludes with an epilogue written by her mother which recounts that Francesca died from a broken heart a year after Giovanni’s disappearance. Clearly, this story was rooted in Lee’s own experiences, but diverges from her true life abruptly, creating a story that is part fact and part fiction—much like the Nutshells themselves.

In turn, Lee’s own work with the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine would ultimately have an influence on 20th century crime writing. Erle Stanley Gardner (1889–1970), of Malden, Massachusetts, was Lee’s contemporary and an attendee at her seminars. Gardner had been writing his well-known Perry Mason detective stories since the mid-1930s, and may have found new material through his engagement with the Nutshells at the police seminars. He wrote a moving obituary for Lee, citing her influence on his work. The Perry Mason story The Case of the Dubious Bridegroom (1953) is dedicated to Lee. The 21st-century obsession with crime film and television, often rooted in forensic analysis, can be said to have roots in Lee’s determination to professionalize the field of crime scene investigation. Beyond her obvious interest in literature and the crafting of complicated narratives, Lee expressed great creativity in her physical creation of the Nutshells themselves. She conceived of each scene herself and then enlisted the assistance of carpenter Ralph Mosher (and later his son Alton Mosher) to help make her vision a reality. The dioramas themselves are a combination of individually made wooden elements, commercially sources dolls’ house materials, and fabric made by Lee herself. She is said to have hand-knitted many of the stockings and clothing for her dolls herself with tiny needles (Botz 2004, 32f.) Lee knew that for the Nutshells to function as teaching tools, she had pay careful attention to every detail—any mis-made or mis-represented element might ‘spoil’ the illusion of the crime scene. Her choice to work on a miniature scale, in this way, raised the stakes concerning the realistic nature of her dioramas.

Mid-century social issues

Made in the late 1940s and actively used in Boston through the 1960s, the Nutshells are an excellent reflection of the social issues pervading America in those decades, such as social paranoia, questions of the safety of new suburban neighborhoods, and the changing role of women in the home. In the years following the end of the Second World War, the American social landscape changed dramatically. Women, who had the opportunity to work outside of the home as part of the war effort, returned to the domestic sphere. Increased wealth and the baby boom spurred a move from urban centers to new suburbs outside of cities. A general wariness pervaded the nation in these years: McCarthyism prompted people to look upon their neighbors with suspicion (Howe 2008, 34). Numerous legislative acts of the 1940s and early 1950s had allowed the government enhanced methods of surveillance for the purpose of national security.9

Lee’s Nutshells bring these concerns into stark—but approachable—reality. The miniature scale renders their topics more palatable, though their points still come across. Her particular focus on violence against women in the home has been controversial. Many of the victims in the Nutshells are female and died in their homes, or even in their beds—the place where we are all most vulnerable. Scholars have questioned whether Lee perpetuated a stereotype of women as victims, or if in fact she was ahead of her time in drawing attention to their vulnerability and the lack of visibility of domestic violence (Botz 2004, 38). Similarly, a number of the studies feature lower- or lower middle-class individuals. This choice can be seen, in the work of a wealthy heiress, as potentially pejorative or disapproving. Yet seen from the other side, Lee was highlighting an underserved portion of the public, whose deaths might not have received the same attention as upper class individuals. With perspective, it is now clear that she was raising awareness about these types of crimes and challenging her student detectives to look beyond the obvious.

The overwhelming majority of the Nutshells feature some degree of voyeuristic interest. The voyeuristic eye often comes in the form of witness statements by neighbors of the deceased. These constantly watching eyes – our neighbors – speak to the inherent contradiction in the nature of the home: a home is necessarily both a public and a private space. The 1940s saw an increase in homes featuring ‘picture windows’ looking in on living rooms: carefully constructed spaces where the family did not actually live, but were to present the vision of a carefully kept home with domestic harmony (Miller 2005, 209). Rumpus rooms or ‘rec’ rooms were the spaces that neighbors could not see.

In one of the most elaborate and large dioramas, Three-Room Dwelling (c.1944-46), the Judson family and their home appear, upon first glance, to be a traditional suburban family from the 1930s or 1940s. The diorama features three rooms – a kitchen and two bedrooms. The porch out front has a child’s toy, as well as milk bottles. Inside the house, the kitchen is well stocked and maintained with a variety of new appliances and name-brand foods. The table is set for the family’s breakfast, complete with high-chair for little Linda Mae. The calm of this rational and ‘typical’ household is abruptly ruptured by the presence of blood splatter through all three rooms, as well as three bodies. Linda Mae is dead in her crib in one bedroom, while the two parents are dead in the other. Kate Judson is in bed and her husband Robert is on the floor beside her. In addition to the abundant blood splatter throughout the house, there is a rifle in the kitchen.

It may be uncomfortable to look upon a domestic setting featuring such violence. This is precisely what Frances Glessner Lee was forcing her student-investigators to do: to look at the home as a site of potential violence and a site worth investigating fully and completely. Lee’s narrative text accompanying this study is detailed. However, neighbors have provided those details. Should the investigator take their witness statement as truth? This focus on the voyeuristic neighbor who watches us reinforces the idea of the modern neighborhood as panopticon.10

Her obvious interest in the living conditions and accessibility to effective law enforcement for lower class urban residents comes across in studies like Dark Bathroom (c. 1944-48) and Unpapered Bedroom (c. 1948), where women are found dead in anonymous spaces in urban boarding homes. Without back stories or families to speak to their past, these urban women are unmoored from their origins and rendered characterless. Even the spaces that they are depicted in are stark, with dull colors and hard surfaces – perhaps a reflection of the bleakness of their lives and prospects in the urban landscape.

Lee displays an equal interest in the lives and crimes of rural America, as can be seen through Woodman’s Shack (c. 1945-48), which features a deceased woman in a dingy log cabin at a lumber camp. Lee spent about half of her time in New Hampshire, in an isolated region of the White Mountains near Franconia Notch, about 150 miles north of Boston. Barns and other rural buildings feature in her focus studies. If medical coroners in urban areas were woefully underprepared for the crimes they would face, rural ones – who might cover a vast territory – could be more so. Lee was particularly concerned about the plight of those who died in rural settings and the inaccessibility of a qualified coroner. Even in the city of Boston, it was often difficult to identify a suitably trained coroner. Harvard Medical School’s Department of Legal Medicine, funded and significantly supported by Lee, proposed new legislation in ten states to require mandatory training for coroners in legal medicine. Though at the time, only two of the states, Maryland and Virginia, passed the legislation, the tide was turning towards a more professionalized field— what we now know as forensic science (Jentzen 2009, 52).

The diminutive nature of the dioramas and the related ‘cute’ attributes of the dolls that inhabit the miniature spaces, makes them at once charming and disarming. By catching the viewer off-guard with their small size, the Nutshells force us to confront very serious themes. Both Lee’s seminar attendees and modern 21st century viewers, such as those who saw the 2017-18 exhibition in Washington, D.C., were prompted to consider ideas of mortality, police bias, and prejudice.

The ‘Nutshells’ and Crime Films

In their aesthetics and in the issues that they address, the Nutshell Studies are very much a reflection of their time. So, too, is the contemporary genre of film noir, which features many of the same characteristics found in the Nutshells. Lee’s ‘characters’ purport to be real people, of their moment, upon which real crimes have been committed; similarly, film noir generally is set in the ‘contemporary’ moment, so that viewers might see themselves within. In film, this rooting in the everyday reinforces the idea that villains and criminals are just as likely to be normal everymen as they are to be crazy monsters at the fringes of society. Lee, too, pushes her investigators to consider that unlikely people—an apparently happily married man, a housewife—may have committed a crime.

Lee in her instructions for the seminar attendees states the following: “Because continuous action cannot be represented, each model is a tableau depicting the scene at the most effective moment, very much as if a motion picture were stopped at such a point” (Lee n.d.) She recognized that her models would only be able to show a brief snapshot of action and so chose the moment of most importance. Her association of her models with motion pictures is apt, as there are many parallels between the themes and aesthetics of the Nutshells and contemporary film.11 Three major societal shifts that contribute to the development of film noir are all important elements of Lee’s work as well: the idea that crime is entrenched and with origins unknowable; the destabilization of gender dynamics after Second World War; and the urban city as a place of crime, prompting middle-class flight to a seemingly-safe suburbia (Luhr 2012, 21). By examining the Nutshells and film noir in parallel, it becomes clear that, in reflecting their moment, they speak to the unease of post-war America. In particular, Alfred Hitchcock’s films Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), and Vertigo (1958) all address themes of voyeurism, crime, and uncertainty about society found in the Nutshells.

The earliest of these films, Rope, plays with the conventional detective story method of letting the viewer know ‘whodunit’ – the murder – right from the start, a common feature in film noir (Luhr 2012, 1). We, as viewers, know what transpired, but the other characters in the film (aside from the perpetrators) remain in the dark. Two friends murder their acquaintance and proceed to host a dinner party around (and upon) the hidden body. As the film unfolds, the good guy – actor James Stewart – plays the role of the investigator, slowing uncovering what happened, and we as viewers see the evidence as he discovers it. In the film’s climax, Stewart explains how the murder happened as the camera pans over the scene of the crime. This ‘aesthetic of the aftermath’ (Rugoff 1997, 18f.) is a common feature in art in the 1940s and 50s, with artists depicting the results of a crime, destruction, etc. Edited to appear as though the film is a continuous shot, it appears to unfold in real time, with the whole film only 80 minutes long. The viewer, therefore, experiences the crime, the aftermath, and the crime solving, in step with the murderers. This trope reflects Hitchcock’s earlier work in Rebecca (1940), where the camera similarly explored the crime scene as the main character uncovers what happened. However: “Representations of dying are not violent because we the viewer are at the safe position of the spectator (voyeur). Severing of the body from its real materiality and its historical context into a fetish” (Bronfen 1992, 44).

Hitchcock’s films instill fear or terror in their viewers precisely because they are set in the modern day, in settings that are recognizable. Lee also exploits a viewer’s search for himself in everything he sees, and made Nutshells that feature members of every station of life, from lower to upper class and localities from urban to rural. Voyeuristic neighbors, which feature in ten of the eighteen surviving Nutshells, are a key feature of the film Rear Window. The injured documentary photographer L. B. "Jeff" Jefferies (actor: James Stewart) is stranded, recuperating at home, with only the view through his window towards the rear-facing windows of his neighbors’ homes to entertain him. His view reveals a typical Greenwich Village neighborhood of four or five story apartment buildings, all facing onto a shared courtyard – which is notable as a film set specifically because it records a very ordinary view (Miller 2014, 157). Jeff comes to believe that a woman has been murdered in one of the homes and becomes obsessed with watching his neighbors, to gather evidence and make his case to his police detective friend, Doyle. The moment of greatest drama comes when his neighbor looks across the courtyard and sees him, reinforcing the idea that voyeurism goes both ways. Rear Window is restricted to Jeff’s view point (Stam & Pearson 2009, 206). So too are the Nutshells restricted to what Lee shares with her ‘investigators’, both in terms of visual clues and background information. This way in which the neighbor becomes someone who might – at any moment – be watching us, witnessing our crime, sets neighborhoods up as a place that serves to self-police. This theory, particularly as it relates to Rear Window has been explored by Bran Nicol. He writes:

The neighbor is someone who regulates our existence, in a way which upholds social and moral norms and might also assist official disciplinary systems. To have a neighbor is to be aware that what we say or do can be overheard or witnessed, and this modifies what we do or say and how we act or speak (Nicol 2010, p. 196).

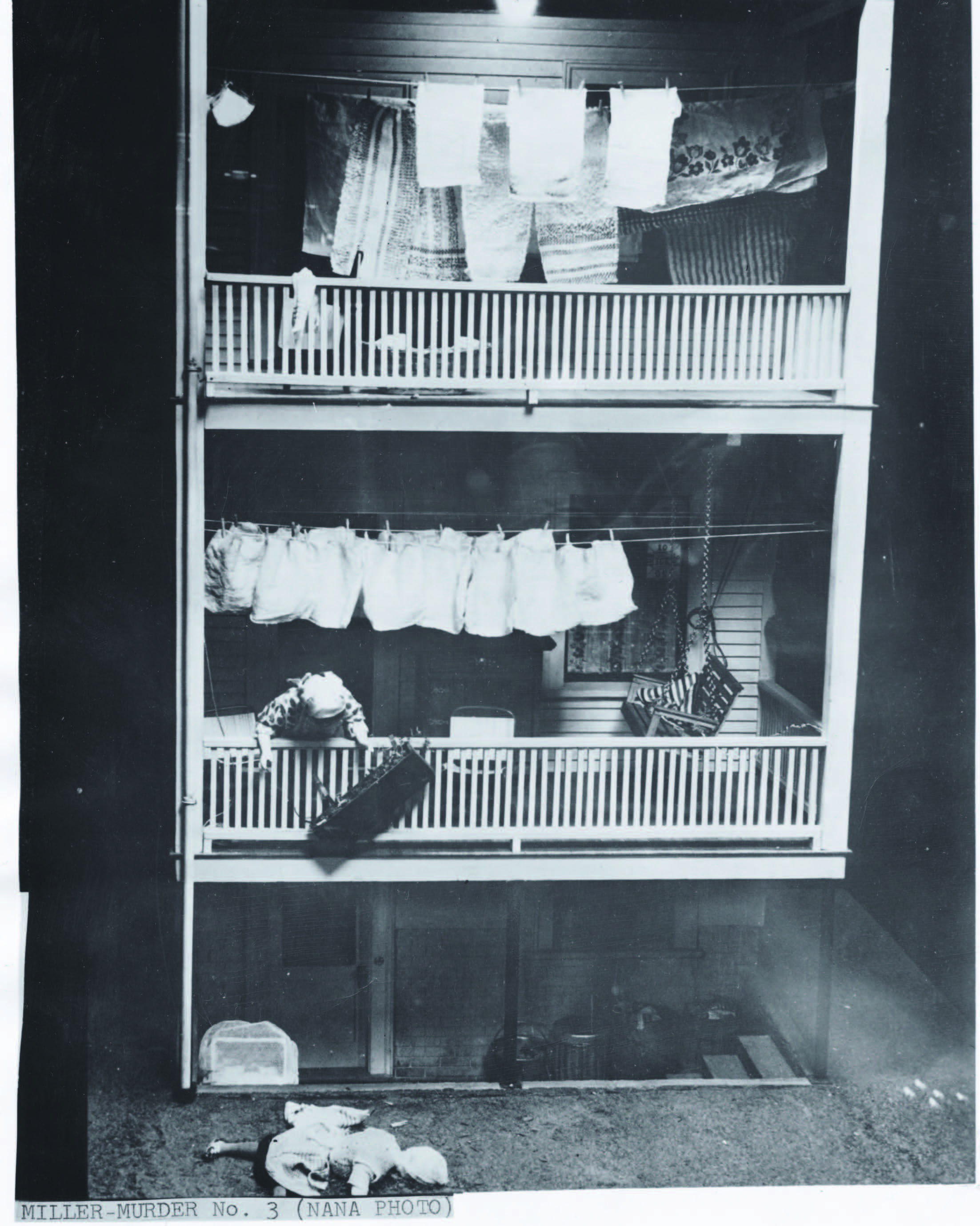

Figure 2: Nutshell Study “Two-Story Porch” taken 1961, Courtesy Glessner House

As with Jeff in Rear Window, amateur sleuths often catch things that the official police might miss. Lee’s own role within the police community, as someone not officially trained in the field, but actively trying to improve and enrich it, parallels the sleuthing of neighbors. Bran Nicol discusses at length the modern American neighborhood as panopticon and effective structure for surveillance and crime reporting (see Nicol, 2010). However, Lee’s Nutshells also offer the cautionary tale that while neighbors can be useful sources of information and key evidence, their inferences and insinuations might likely come from a voyeuristic intention – not always the clear-headed and factual approach required by law enforcement. In Two-Story Porch, (c. 1948) a housewife, Mrs. Morrison, is found dead on the ground below a high balcony (see figure 2). When the police arrive at the scene, her neighbor Mrs. Butler is eager to tell them that the Morrisons fight often and loudly. If the police were to take this at face value and not fully investigate the crime scene, they would miss critical physical evidence that points not towards a murderous husband who pushed his wife to her death, but to the real manner in which Mrs. Morrison fell. With laundry hanging and chairs and toys lying around, the porches look very mundane and recognizable. Further underlying the quotidian quality of this scene, the two-story house resembles homes still seen in residential neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city of Boston. In Vertigo, the unease and imbalance of this period of American life is manifested in the main character, again played by James Stewart. Post-war opportunities drew people of many backgrounds to the cities. The disorientating and fleeting quality of an interaction in the city- so vividly portrayed in Vertigo- is paralleled in the Nutshell Unpapered Bedroom (c. 1949-52), where the female victim is only identified by a pseudonym. Lee’s Nutshells, like Hitchcock’s film, make manifest the fear of anonymity in the lawless city center. All three films discussed here, as well as the related Hitchcock film Rebecca, are based on literary sources. Lee’s intense creativity in constructing imagined worlds, characters, and crimes – in both physical settings and in words – bears clear evidence of her literary tendencies.

Conclusion

Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death of the 1940s and 1950s are a direct reflection of the social climate of their day. By addressing issues of urban and suburban life, social class, femininity and gender, the changing nature of the home, and death, the Nutshells bring to light many of the concerns of mid-20th century America. Lee intended her Nutshells and the Harvard Department of Legal Medicine’s program to push medical schools, coroners, and crime scene investigators to recognize the need for professional training in the field. By crafting miniature, and more perfect, versions of both actual and imagined crime scenes, Lee didactic tools which were valuable in both their own time and have a lasting impact for students of forensic science today. Alfred Hitchcock’s crime films of the same period, in particular Rope, Rear Window, and Vertigo, similarly bring to life these concerns. Both makers choose to situate their crimes firmly in contemporary places, filled with familiar scenery and objects. In this way, both the Nutshells and the films firmly root their viewers in a world where crime is so pervasive as to be inescapable. In the way that a film is a condensed, framed experience, so too do the Nutshells create a choreographed and curated viewpoint. By nature of their miniature format, they distill the essentials of the action to its core and essence, achieving a more striking effect.

[1] This article arose from 2017-18 research on the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I am grateful to many colleagues at the museum, but in particular Carter Long of the Film Department for his insights and Adam Tessier for his guidance and editing.

[2] Thanks to William Tyre of the Glessner House Museum for information about the Glessners’ marriage, working relationship, and domestic life at the Glessner House.

[3] Thanks to Linda Herrman of the Bethlehem Heritage Society of New Hampshire for providing access to Frances Glessner Lee’s childhood writings.

[4] The World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago from May 1 to October 31, 1893. Organized to celebrate the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America, it drew over 27 million visitors – nearly triple the attendance of the Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876. For its six months run, the fair brought art, architecture, manufactory, and curiosities from around the world to Chicago. Held in Jackson Park in South Chicago, the fair captured the imagination and interest of America beyond Illinois. Estimates suggest 25% of the country’s population visited the fair, where they would have seen the huge buildings in plaster of Paris, which gave the fairgrounds the nickname ‘The White City’.

[5] The Harvard Museum of Natural History has a collection of over 4,000 glass models representing 830 plant species. The project was initiated by botanist George Lincoln Goodale in the 1880s, who sought accurate reproductions of plants for use in teaching. The models were created by the father and son team of Czech glassmakers Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka in their studio near Dresden before they were shipped to Boston. While the models are full size replicas of plants, rather than miniatures, the way that they record plants in a fixed, permanent, and idealized manner parallel’s Lee’s desire for the Nutshells.

[6] The exhibition, titled “Murder is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death’ was at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. from October 20, 2017 to January 28, 2018: https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/nutshells.

[7] The Harvard Associates in Police Science, Inc. is based in Baltimore, MD and hosts an annual conference: http://harvardpolicescience.org/conference/.

[8] Consider the Boston College School of Nursing’s Simulation Center, where students work with both animatronic mannequins who exhibit symptoms and must be treated and with scenarios which display the aftermath of a crime scene to be combed through for evidence. Thank you to Jeanie Foley, Assistant Director of the Simulation Center, for sharing information about their program.

[9] For an extended discussion of the relationship between post-war surveillance, McCarthyism and Rear Window, as well as Hitchcock’s other works see Corber (1992).

[10] For an extended discussion of the modern American neighborhood as panopticon—a system of self-policing where we expect our neighbors to be watching us at all times—see Nicol (2010).

[11] The Harvard Department of Legal Medicine’s ties with film culture extend beyond Lee’s own thoughts that her Nutshells related to motion picture action. The 1950 feature film Mystery Street, directed by John Sturges, originally began as a documentary on the Legal Medicine department, but was changed to be a detective drama. However, the film still retained elements of the new forensic science techniques that the department promoted. Lee would surely have been aware of the film.

Literaturverzeichnis

Primary sourcesGlessner, John Jacob (2011). The Story of a House. Chicago: Glessner House Museum.

Lee, Frances Glessner (n.d.). Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Notes and Comments. Unpublished manuscript in the archives of the Harvard Medical School Countway Library of Medicine.

Secondary sourcesBotz, Corinne May (2004). The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. New York: Monacelli Press.

Bronfen, Elisabeth (1992). Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity, and the Aesthetic. New York: Routledge.

Corber, Robert J. (1992). Rear Window and the Limits of the Postwar Settlement. In boundary 2, Vol. 19, No. 1, New Americanists 2: National Identities and Postnational Narratives (Spring, 1992), pp. 121-148.

Howe, Lawrence (2008). Through the Looking Glass: Reflexivity, Reciprocality, and Defenestration in Hitchcock’s “Rear Window”. In College Literature, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Winter, 2008), pp. 16-37.

Jentzen, Jeffrey M. (2009). Rockefeller Philanthropy and the Harvard Dream. In Jeffrey M. Jentzen, Death Investigation in America: Coroners, Medical Examiners, and the Pursuit of Medical Certainty (pp. 31-52). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Luhr, William (2012). Film Noir. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Miller, Laura J. (2005). Denatured domesticity – An account of femininity and physiognomy in the interiors of Frances Glessner Lee. In Hilde Heynen and Gülsüm Baydar (Ed.), Negotiating Domesticity: Spatial Productions of Gender in Modern Architecture (pp. 196-212). London: Routledge.

Miller, Nicholas Andrew (2014). “Dear Miss Lonelyhearts” – Voyeurism and the Spectacle of Human Suffering in Rear Window. In Mark Osteen (Ed.), Hitchcock and Adaptation: On the Page and Screen (pp. 127-143). Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield.

Nicol, Bran (2010). ‘Police Thy Neighbor’: Crime Culture and the Rear Window Paradigm. In Patricia Pulham et al. (Ed.), Crime Culture: Figuring Criminality in Fiction and Film (pp. 192-209). London: Bloomsbury.

Rossi-Wilcox, Susan M. (2015). A Brief History of Harvard’s Glass Flowers Collection and Its Development. Journal of Glass Studies (57), pp. 197-211.

Rugoff, Ralph (1997). Scene of the Crime. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stam, Robert and Roberta Pearson (2009). Hitchcock’s Rear Window: Reflexivity and the Critique of Voyeurism. In Marshall Deutelbaum and Leland Poague (Ed.), A Hitchcock Reader (pp. 199-211). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Stewart, Susan (1993). On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press.

About the author / Über die Autorin

Courtney Leigh HarrisCuratorial research fellow for decorative arts and sculpture in the Art of Europe department at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston where she has worked on a number of projects related to miniatures. She holds her B.A. in History of Art and International Studies from Johns Hopkins University and her M.A. in History of Art from the Courtauld Institute of Art, with a specialization in the Arts of Florence and Central Italy from 1400-1500. Prior to the MFA, Courtney worked as a provenance researcher at the London-based Commission for Looted Art in Europe.

Korrespondenz-Adresse / correspondence address:

charris@mfa.org