denkste: puppe / just a bit of: doll | Bd.3 Nr.1.2 (2020) | Rubrik: Fokus

Barbarella – Toying with Anticipations.

Un/Fashioning Dolls and Androids in the Early Comic Strips of Jean-Claude Forest and Roger Vadim’s Film Adaptation1

Barbara M. Eggert

Focus: Puppen/dolls like mensch – Puppen als künstliche Menschen

Focus: Dolls/puppets like mensch – dolls/puppets as artificial beings

Abstract:

In Jean-Claude Forest’s first Barbarella comics (1962–64), as well as in Roger Vadim’s

film adaptation (1968), space agent Barbarella experiences adventures with various

species, including dolls, artificial soldiers and an android – some of them erotic,

others of a martial nature. Barbarella’s (partial) loss of clothing during these encounters,

along with her changes of garments, form caesuras in the visual narration on the one

hand, while on the other hand her textile performances are addressed to extradiegetic

viewers to whom the heroine is presented as a dress-up doll. Focusing on Barbarella’s interactions

with artificial humans, this contribution contextualizes comic-strip panels and

film sequences that frame the (partial) unclothings and analyzes their narrative functions.

Following on from Donna Haraway’s Cyborg’s Manifesto (1985), Barbarella’s transmedial

bodily exposures in comics are interpreted as a form of egalitarian trans-species interaction,

while the film is repositioned as comedy/parody.

Schlagworte: Barbarella; fashion; transspecies interaction

Zitationsvorschlag: Eggert, B. M. Barbarella – Verpuppte Erwartungshaltungen. Ent/Kleidungen Von Puppen Und Androiden in Den frühen Comicstrips Von Jean-Claude Forest Und Der Filmadaptation Durch Roger Vadim. de:do 2020, 3, 61-69. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/5623

Copyright: Barbara M. Eggert. Dieses Werk steht unter der Lizenz Creative Commons Namensnennung – Weitergabe unter gleichen Bedingungen 4.0 International. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.de).

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25819/ubsi/5623

Veröffentlicht am: 20.10.2020

Um auf Zusatzmaterial zuzugreifen, besuchen Sie bitte die Artikelseite.

Barbarella – whose doll is she?

To many comics scholars and fans (not to mention lawyers), l’age adulte –

the period in which European comics became recognized as an adult medium

– began in April 1962 with the publication of the first Barbarella

adventure, which was drawn and written by Jean-Claude Forest2 (Mazur & Danner

2014, 93). The space heroine’s first eight adventures were initially serialized in

V Magazine, then published by Éric Losfeld as a 68-page album in 1964 by his

own publishing company, Le Terrain Vague.3

Its erotic content, or partial nudity, conflicted with a 1949 French law

that was intended to control publications, including comics, that were intended

for young people (Gravett 2014), and the comic was banned. In spite of, or

maybe because of, the censorship debate and its temporary ban, Barbarella the

comic was quite successful and Losfeld’s 1964 edition sold at least 20,000 copies

(Lofficer & Lofficer 1985, 38).4 In 1966, Forest and Losfeld published a slightly

less revealing and slightly more law-abiding version of the album. The first translations

into English and German followed in the same year (Knigge 2016, 25).5

Two years later, a third edition was printed to accompany the release of the Roger

Vadim film.

Vadim’s adaptation, starring Jane Fonda, hit the movie theatres in 1968

and was also very popular, especially in the UK, where it became the year’s

second-highest-grossing film after The Jungle Book (Curti 2016, 85). Both the

comic and the movie were trailblazers in their own ways: Whereas the comic

helped create a new comic category in Europe – adult comics – and was, and

is, regarded as part of a “groundbreaking series of adult science-fiction comics”

(Mazur & Danner 2014, 114)6, Vadim’s Barbarella was – as Alicia Fletcher (2018)

pointed out – “the first female-led work of the science fiction film genre”.

Nevertheless, contemporary film critics did not hold the movie in high-esteem: While its cinematography and design were praised by some (e. g. Malcolm 1968), the script and the film’s general lack of, or, at best, rather juvenile, humor were strongly criticized by others (e. g. Adler 1968; Bates 1969). Its alleged similarity to adult movies, or porn, has been highlighted ever since its release and is still repeated today (cf. Fabris & Helbig 2016, 9; Fletcher 2018). But on what basis? In both comic and film, the curious space agent engages in various encounters with other species, sometimes erotically charged, sometimes charged militarily. Most of these encounters are marked by a voluntary or involuntary (partial) disrobing and/or by Barbarella’s choice of another dress. Using close reading and close watching, the paper contextualizes comics panels and film sequences that frame (partial) unclothing and switching clothes and analyzes their narrative functions with a focus on Barbarella’s interaction with artificial humanoids such as dolls, phantom soldiers, and an android. In a broader context, it also raises the question of how much Barbarella herself is presented as a kind of doll in both media.

All dolled-up? The semi/naked truth about Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella (1964)7

In the first eight episodes of his comic series Barbarella, Jean-Claude Forest introduces his heroine as someone who doesn’t shy away from using firearms to defend herself or a noble cause for the benefit of others. Whereas even high-tech guns tend to be unreliable, the space agent can rely on other, built-in sources: As scholars including Parks (1999, 263) and Lathers (2012, 170) have pointed out, with respect to the movie, Barbarella’s real weapon – her ‘technology’ – is her body, metaphorically turning her into a hybrid of an automaton such as E. T. A. Hoffmann’s bewitching Olimpia (The Sandman, 1816) and a combat robot. But whereas the latter’s technology is usually clad in armor and therefore invisible, and Olimpia’s mechanics are revealed only by accident as she falls apart, Barbarella’s technology is on display all the time – but not as unveiled as rumor has it. Befitting the materiality of the comics medium, that is, paper, her continual changes of attire make Barbarella more of an eroticized paper doll than a sex puppet. Can Barbarella hence be defined as an erotic comic? It depends. According to Justin Hall, erotic comics “are works of sequential art with sexual titillation as at least one of their primary artistic intentions” (Hall 2017, 154). But Hall also uses ‘erotic’ as a synonym for porn, and that is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the main, or even exclusive purpose, of sexual arousal. This explains why Barbarella did not make it into his essay, because in spite of its reputation, the comic does not contain much pornographic activity. It is, as will be shown, more of a porn and nudity myth which has a firm grip for decades on the brains of diverse comics scholars of both sexes. Harald Havas, for example, suggests that Barbarella “misses hardly an opportunity to show herself naked or to seduce extraterrestrial and terrestrial creatures of both sexes” (Havas & Habarta 1992, 222), whereas Christine Lötscher is under the impression that “Barbarella’s breasts jump out of her clothes at the least physical effort” (Lötscher 2018, 306).8 Andreas Knigge claims that “never before have comic book characters exposed themselves so unrestrainedly in front of their reader” (Knigge 2017, 6). But are these statements really adequate? How much does the reader of the comic actually get to see of Barbarella’s body, how often and to what purpose?

Looking at the ‘semi/naked truth of Barbarella’, there is hardly any full nudity or semi-nakedness on display, and the presentation of various degrees of cleavage prevails (cf. Table 1).

Table 1: The semi/naked truth about Forest’s Barbarella comic (1964)

| adventure/s | panels | panels depicting (in the order):

|

Context and/or direction of

erotic interests: (m) = mutual (>b) = directed towards Barbarella |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71 | 2 / 19 / 0 / 1 | Dianthus (m?), Ahan (m) |

| 2 | 66 | 10 / 0 / 1 / 2 | Aka Leph (>b), Queen Medusa (>b) |

| 3 | 59 | 23 / 0 / 0 / 1 | Strickno (>b) |

| 4 | 68 | 12 / 2 / 0 / 0 | Prince Topal (m) |

| 5 | 57 | 1 / 5 / 0 / 0 | Pygar (m?) |

| 6 | 63 | 1 / 5 / 0 / 0 | Captain Sun (>b) |

| 7 | 58 | 1 / 0 / 0 / 3 | Diktor (m) + excessive machine + the Great Tyrant/Queen of Sogo |

| 8 | 51 | 6 / 0 / 0 / 0 | – |

| total | 493 | 56 / 3> |

Usually, and not surprisingly, these more or less revealing panels appear in clusters documenting the rhythm of Barbarella’s acts of baring her body (cf. Table 2).

Table 2: The baring rhythm of Forest’s Barbarella comic (1964)

| adventure/s | panels | rhythm: (c) = excessive cleavage / (b) = bare breast(s) (d) = bare derriere (d) / (n) = nude (x) = everything else |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (10 pages) | 71 | xxxx|xxxxxxxx|bbccxxxx|xxxxxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxbbb|bbbbbbn| xxxxbxbb|bbbbbxxxx|xxxxxxx |

| 2 (10 pages) | 66 | xxxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxxx|nndxcxx|xxxxxx|xxxxxxcc|xcxxxxxx|

xcxcxcx|xxxcccc|xxxxcx c = Medusa looking like Barbarella |

| 3 (8 pages) | 59 | xcxx|xxxcxxx|cxcxxcxcxx|ccxxcccc|cxxcxncxc|xcxxxccxx| xxccxxx|xxcxcxc |

| 4 (8 pages) | 68 | xxxx|xxxxxxxc|cxxxxbxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxxxcb|xcxcccxc|cxxcccc| cxxxxxxx |

| 5 (8 pages) | 57 | xxxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|xcbbbxxb| bxxxxxx |

| 6 (8 pages) | 63 | xxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxx|xxxxxxxxxx| xxbxxbbxbx|xxcxxxxxb |

| 7 (8 pages) | 58 | nnnxxx|xxxxxcx|xxxxxxxxxx|xxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxxxx| xxxxx|xxxxxxx |

| 8 (8 pages) | 51 | ccxxx|xxxxxxxx|xxxxxcx|xcxxx|xxxxxx|xxxxxxxx|cxxxcxxc|xxxc |

| total | 493 | (x) = 398; (semi)nakedness: (c) = 56 / (b) = 31 / (d) = 1 / (n) = 7 ⇒ 1 : 4 ratio |

Even if we take cleavage into account, however, the bare-to-clad ratio is a lean

1: 4, so it looks as if Barbarella left out some opportunities for disrobing, especially

in her last adventure. So much for quantity. But how about quality and the

alleged ‘unrestrainedness’ of shedding her clothes? To come to a judgement, I

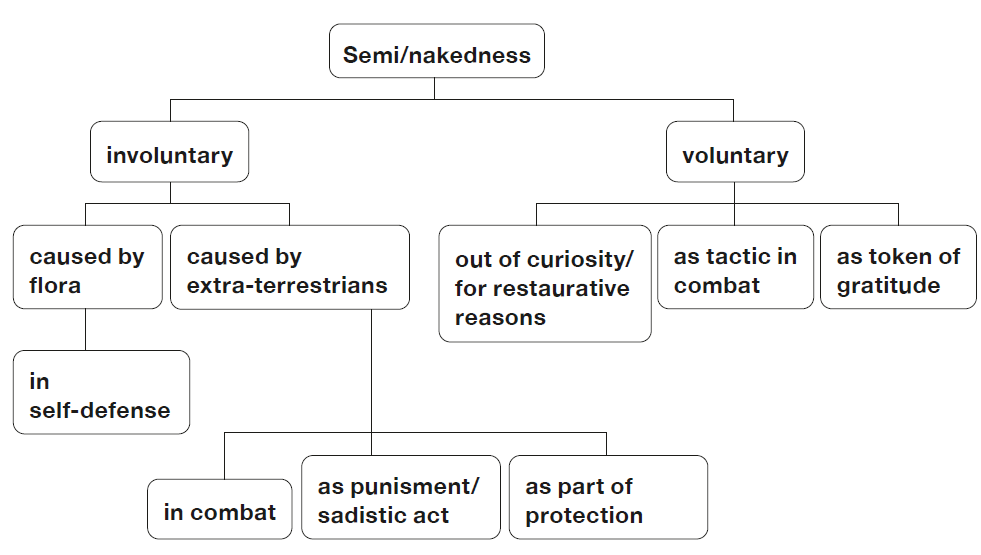

analyzed the different textinternal motivations underlying Barbarella’s shedding

of clothing, starting with distinguishing between involuntary and voluntary acts

of disrobing (cf. Figure 1).

A close reading of Barbarella’s encounters with artificial humanoids includes

examples in all of these categories.

Figure 1: Categorizing semi/nakedness and its purposes in Forest’s Barbarella (1964)

Beware of biting dolls!

Barbarella’s first encounter with an artificial human takes place in Episode 4 (Forest 1964, 29pp.). After escaping the deserts of the planet Lythion in a subterranean rocket, Barbarella enters the region of Yesteryear, which is covered in snow. Still dressed in a fur bikini (groundhog tail), a gift from Strickno, a late admirer (ibid., 25), Barbarella’s mission is to find adequate clothing for the wintery climate. She receives a rather frosty reception by one of the 18-year-old twin princesses of Yesteryear: Though she is all dolled-up and looking harmless in a 19th century-inspired dress, Stomoxys or Glossina9, one of the twin daughters of King Aranrabal, lands a snow-ball in Barbarella’s face. Though warned by her travel companion, the scientist Klill, Barbarella approaches the princess to teach her a lesson, only to be bitten by the girl’s doll. This doll had been visible in two previous panels, hanging limply beside the princess (Panel 1) and then hidden behind her back (Panel 4, directly underneath Panel 1). As an accessory, the doll gives her owner a rather childlike air – but only at first sight. In the centre panel of the page, we see nothing but Barbarella’s bare arm, ready to slap the princess when met and stopped by the doll’s teeth in mid-air. Like her owner, whose hands are visible in the same panel, the toy weapon is dressed in 19th century-style but also shows a strange resemblance to Barbarella because of the colour and length of its hair. This slapping incident sets the narration in motion, as Barbarella chases after the princess only to be caught by the evil twins, who bring their prey to their family’s castle. As her fur bikini wasn’t cut out for such activities, the top has long since disappeared when a handcuffed Barbarella is rescued by Prince Topal, the twins’ handsome elder brother (ibid., 30). He not only helps the visitor from Earth to a steampunkish version of 19th century fashion, but also introduces her to his father, the king. Together with the nobility of Yesteryear, a fully clad Barbarella embarks on a Zeppelin tour which is sabotaged by the evil twins. Literally having jumped (air-)ship with the prince and having solid ground underneath her feet again, Barbarella wants to show her gratitude to Topal by becoming intimate with him (ibid., 33). Their timing is bad, however: In the middle of her (this time) voluntary undressing, the twins show up again, overwhelm their brother and abduct his love interest once more (ibid., 34). Inside the wreck of an old spaceship, they introduce Barbarella to their mean friends. For their amusement, their captive, now in high waisted, skin-tight torero pants and a strapless bra, is towed to a tube like a camp version of a Christian saint about to be tortured or fed to wild beasts in the Colosseum (ibid., 35). But instead of wild animals, she is again threatened by toys a mechanical soldiers and puppets who are “hungry like wolves” (ibid.) are set loose. These toys might well be a perverted allusion to automata toys of the Victorian era – or to E. T. A. Hoffmann’s winter tale The Nutcracker and the Mouse King (1816), which also features mechanical toys, including dolls and soldiers. Mario Petipa’s ballet adaptation of this work premiered at the Imperial Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1892. Since then, watching the ballet has become an international Christmas tradition. As the ballet also features a Spanish dance, this would explain Barbarella’s torero outfit. A creature that resembles a mechanical turtle is already stuck on Barbarella’s thigh and works its teeth into the fabric of her pants, but before a puppet that looks like a miniature version of the evil twins can attack her as well, Prince Topal again interferes (ibid., 36). Like St. Martin, he has a coat to bestow on Barbarella. In spite of Prince Topal’s endearing chivalry, Barbarella leaves soon afterwards, fed up with Stomoxys and Glossina’s assaults – and, dressed as an ice princess, rushes to her subterranean vehicle and toward a new adventure, in which she is again on top of things.

Fighting empty armors

Episode 5 (Forest 1964, 37pp.) takes Barbarella to a labyrinth in front of the cursed city of Sogo. This is where Duran, a former fellow earthling, and his comrades in fate exist in despair. Constantly threatened by the soldiers of Sogo, who look like massive gladiators in leathery suits of amour with weapons to match, such as pikes and whips. Barbarella wants to help her new friends Duran and the blind ornithanthrope (bird man) Pygar escape this desperate place and decides to confront three soldiers who guard the labyrinth all by herself (ibid., 42p.). Like a sci-fi version of an Amazon, she strips off the top of her space suit to confuse them. This strategy works, and she finishes off two of them. This act of undressing cannot be classified as “unrestrained”, and there are no “breasts breaking free” by accident. Barbarella uses a tactic to achieve her strategic aim, and she also applies it successfully in two episodes with animated counterparts. When her firearm jams after two shots, Pygar and Duran join her and fight the third soldiers together – only to discover that the soldiers consist of nothing but empty leather shells which had made them appear to be humans clothed in armor. Until then, unbeknownst to her, Barbarella’s ‘technology’ also works on humanoids.

Mechanical pleasures

Apart from the accidental and involuntary hostile encounters with artificial humans

which coincide with either involuntary passive destruction of her clothes

or the voluntary shedding of clothes as strategy for duping an adversary or as

a diversionary maneuver, there is a third disrobing motif: sexual curiosity. The

seventh episode (Forest 1964, 53pp.) begins with a naked Barbarella in bed with

an equally undressed android Diktor. This is one of only three sequences starring

a textile-free heroine – and the only one with an android by her side.10 Forest drapes his heroine and her android lover suggestingly rather than suggestively,

whereas the tender or wild previous moments and the possibly unrestrained act of

undressing are left to the imagination of the readers and comics scholars.

Apart from being a side effect of sexual curiosity or combat, another reason

for voluntary disrobing is often mingled with the first: After being rescued, the

adventuress Barbarella likes to offer intimacy as a token of gratitude. Diktor rescued

her in the fifth episode (Forest 1964, 45pp.) by giving her a ride in his air

taxi to escape from Sogo while bullets flew around them (ibid., 52). Appreciating

his capacity to dodge this attack, she asks the gentleman android with the bow

tie about his other qualities. Diktor promises many other qualities – and no disappointments.

Apparently, he accepted Barbarella’s gratitude and curiosity and,

judging by the conversation they have while Diktor is getting dressed, he did not

exaggerate his abilities.

Except for Ahan and Diktor, though, Forest does not let his heroine become

too successful when it comes to delivering her intimate thank you notes. In the

first adventure, her timing with Dianthus is bad, and the same goes for her later

adventures involving Dildano, Captain Sun, Prince Topal, and Pygar.

In summary, Barbarella the comic can hardly be called porn. Neither full

nor partial nudity, nor anything in between, necessarily leads to the display of

intradiegetic

sexual activity. There are different motivations for partial nudity,

which is at least ambivalent because it can be either a threat or a reward.

It is always a treat for the readers, but with rare exceptions is not shown ‘just

because’. Whereas Barbarella might be construed as a character who suggests

“unrestrainedness”, Forest is rather discreet in communicating this visually. So,

it is rather the irrepressibility of the comics readers’ and scholars’ minds when it

comes to filling the comic’s gutters with their own imaginations, especially when

Barbarella’s ‘technology’ doesn’t get enough attention on a textinternal level. By

constantly presenting Barbarella in different costumes which are revealing and

veiling at the same time, Forest makes Barbarella into a paper doll to toy with his

readers’ anticipations.

Dare to be bare? ‘Barbarella’ the movie

Barbarella the movie is based on the first eight adventures of the sci-fi comic heroine. Forest himself was involved in the film’s design and helped with the script, which explains its closeness to the comic. The movie is not very daring when it comes to baring – neither under today’s standards nor those of the 1960s. Full nudity is limited to the opening sequence and to the aftermath of Barbarella’s first encounter with her rescuer, Mark Hand, the catch man (compare Lembcke 2010, 68p.). Both times, Jane Fonda’s body is strategically covered. In the opening sequence the credits function as a filter and ‘prevent an X rating’ (Fletcher 2018). In the minutes which follow, as a naked Barbarella talks to her boss Dianthus, president of the universe, the 5-star double-rated astro navigatrix either has her back towards the audience, is shown in close-up from head to collar bone, or holds props such as weapons in her arms. She is “Armed, like a naked savage!” as Barbarella puts it. In the other scene with X-rating potential, Fonda’s Barbarella-body is blurred by partially transparent plastic tube she crawls through on her way to the catch man’s wardrobe. Apart from these two episodes, there is only suggested nakedness. After having bestowed the will to fly again on ornithanthrope Pygar, Barbarella is covered in moss and feathers. And the only actual love making that the audience witnesses happens between Barbarella and the rebel leader and self-acclaimed boy toy Dildano in the style of terrestrials in the 41st century – fully clothed with hardly any physical contact, medically aided by pleasure pills with hair-raising or, in Barbarella’s case, hair curling, effects. Barbarella’s naked encounter with the excessive machine (orgasmatron) is not revealing either, because she appears as a ‘dea clad in machina’ and, after having unwillingly destroyed the orgasmatron, rises from it fully clothed. Compared to the comic, the set of categories for narration-related reasons for shedding clothes (cf. Figure 1) has been stripped down. The category of baring on purpose in combat, for example, was dropped entirely. Disrobing as a token of gratitude occurs only twice, with Mark Hand and with Pygar. The adaptation has no Diktor in it. In her essay Space Oddities, Marie Lathers (2012, 170) points out that “You saved my life is code for ‘let’s have sex’”. But this code is not used very often.

Textile de/constructions

What does happen very often during the movie is an – on Barbarella’ s part involuntary

– partial destruction (or should we say ‘deconstruction’?) of her clothes in

combat. The movie adopted the comic’s biting dolls as well as the empty armor

from Sogo as dress menaces (cf. Table 3).

In his 1976 essay The Pleasure of the Text, Barthes writes, “Is not the most erotic

portion of the body where the garment gapes? There are no erogenous zones; it

is intermittence which is erotic” (Barthes 1976, 9). And the movie offers a lot of

erotic intermittence, even more than the comic. In her book Acts of Undressing,

Barbara Brownie (2017, 44) writes that “sexual curiosity is sparked by intermittent

exposure of any part. Intermittence has the power to re-chart the erotic map

of the body”. Intermittence occurs in the state of Barbarella’s disarranged clothing toys, with the viewers’ anticipation that this might lead to full unclothing. But destroyed

clothing always leads to new dress. The ripped clothes on Fonda’s body do

indeed seem to permit the fantasy of undressing or removing the garment completely.

However, except for the opening sequence and Barbarella’s adventure with the

catch man, these fantasies are never fulfilled. Barbarella decently undresses and

dresses behind screens or is otherwise fully screened, as in the scene with the

orgasmatron, which also serves as a discrete changing zone.

Since Fonda sports as many as eight different outfits during the movie’s 94

minutes, the destruction, deconstruction and loss of clothing seem to be excuses

for justifying a change of dress. And dresses are never just dresses – they are

signifiers and function a communication technology as they reflect Barbarella’s

role in each episode.11

The space suit (1) of the opening scene is not only necessary for the airstrip,

but it also marks Barbarella as an astro navigatrix; for dreaming and sleeping,

there is a special garment (2). For exploring a winter landscape, Barbarella dresses

as a mixture of ice princess (dress) and superhero (cape) (3). The fur she picks

from Mark Hand’s wardrobe stands for her experience with old-fashioned sex (4);

she is dressed in white when she meets the angel (5); is clothed in a mixture of

Jeanne D’Arc and superheroine for her trip to Sogo (6); mingles with the natives

in a local costume (7); and finally dresses in futuristic Robin Hood-meets-Peter

Pan style when helping to lead the rebellion against the evil queen (8). As Fonda’s

dresses were made by Paco Rabanne (Ward, 2017, esp. 31, 34) and Jaques Fonteray

(Lundén, 2016), one could also argue that the movie functions as a fashion show in

disguise with the actress as a mannequin, a living doll, to show them off.

Table 3: Veiled undressing in Roger Vadim’s Barbarella movie (1968)

| Chapter & spatial context | time code | state of undress (v )= voluntary (iv) = unvoluntary) |

(erotic) counterpart (m) = mutual) (⇒b) = directed towards Barbarella |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 // inside of space ship > statue of Diana | 00:00:28–00:04:36 | „air strip“ 0 %–100 % (v), captions as coverage | movie goers (⇒b) |

| 2 // inside of space ship | 00:04:36– 00:08:36 | „affair of the state“ 100 %, visibility: upper body, mostly from behind | President Dianthus (m?) |

| 4 + 5 // Tau Ceti / attac of killer toys | 00:18:08– 00:24:08 | damaged stockings and mid rim, thighs and behind (iv) | evil twins, other evil kids |

| 6 // Sledge of Mark Hand | 00:24:17–00:25:20 00:25:21–00:25:40 00:25:43–00:25:51 |

100 % (v/iv) screened by plastic tube later by skunk fur |

Mark Hand, the catch man |

| 7 // Sogo / labyrinth | 00:37:50–00:38:20 | damaged unitard, mid rim | movie goers (⇒b) |

| 8 // Sogo / nest of Pygar | 00:38:21–00:39:26 | 100 %, covered in moss & feathers | Pygar |

| 13 + 14 / Sogo / bird cage | 00:58:38–01:05:28 | damaged stockings and mid rim, thighs and behind (iv) | Dildano |

| 16 / Sogo / excessive machine | 01:14:23–01:18:40 | 100 %, covered by machine | Durand Durand |

Conclusion

As we have seen, Barbarella is not, as Lembcke calls her in Hanoi Jane, an

“underdressed superwoman” (Lembcke 2010, 63) but, rather, a woman who is

dressed appropriately for any situation, textile allusions to superheroines pretty

much intended. Indeed, in the music accompanying the airstrip sequence, Barbarella

is referred to as ‘wonder woman’, one of the superheroines. In the movie,

her super power is her innocence, which saves her and, ironically, also saves the evil Queen of Sogo from a bad ending. But whereas superheroes usually lose their

powers when their costumes are ripped, as described by Brownie and Graydon in

their book The Superhero Costume. Identity and Disguise in Fact and Fiction

(2015), in Barbarella’s case the un-intactness of the costume only endangers

others and always leads to a solution to her plight, suggesting that her real costume

is her own skin. This message of the comic is watered down in the movie, as

is the ambivalent message of the flashing of Barbarella’s body, which could mean

either pleasure or danger. In the comic, Barbarella uses her body to communicate

and cohabitate one way or other with all kinds of creatures, including mythological

beings representative of the past as well as a robot representative of the future.

When she sheds her clothes, Barbarella also sheds concepts such as otherness and

heteronormativity, sporting egalitarian views of humans, cyborgs, and anything

in between, regardless of what to her a merely peculiarities, such as race and

gender. Therefore, Barbarella the comic can be seen as the precursor to Donna

Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1985), in which Haraway does away with troubling

binaries such as human / non-human, active / passive, male / female, etc., which

“have all been systemic to the logics and practices of domination of women” and

“all constituated as others” (ibid., 59). As Haraway’s imagined feminist, Barbarella

others nobody but, rather, is busy “building and destroying machines,

identities, categories, relationships, space stories” (68), sometimes even literally.

In the end, the futuristic nature of both the comic and the movie is at least twofold:

on a textinternal level, the story is set in the 41st century, but in extradiegetic

history it also anticipates feminist theories of the 1980s.

This feminist reading that might occur – against Forest’s grain – leads to

a new evaluation of Barbarella’s physical and textile language in both film and

comic – an intriguing challenge I hope to pursue much more deeply in research

to come.

[1] I would like to thank Anne Dorfman, Esq., for helping me with the language. This contribution is dedicated to Linda Novotny.

[2] Jean-Claude Forest (1930–1998) studied at the École des Arts et Métiers in Paris. As of the 1950s, he started working as a freelance illustrator for comic magazines. It wasn’t until his first episode of Barbarella for V Magazine that he gained recognition as a comic artist.

[3] Le Terrain Vague specialized in surrealist authors such as André Breton, Léo Malet, and Boris Vian as well as literature on film theory (Knigge 1996, 260).

[4] Gravett (2014) mentions about 200,000 copies sold, which is more likely to equal the whole printrun.

[5] Three more volumes followed in 1974, 1977/78 and 1981 respectively, but it was the first eight adventures which inspired Roger Vadim’s feature film Barbarella.

[6] Scholars such as Aidan Power (2017, 94) disagree and categorize Barbarella as “more conventional European sf fare” of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Der schweigende Stern (engl., First Spaceship on Venus, Kurt Maetzig, East Germany/Poland, 1960) and La Decima Vittima (engl., The 10th Victim, Elio Petri, Italy/France, 1965).

[7] For legal reasons, this text includes no panels of the comic. All paraphrases of the text are mine. The complete album in English is available online via http://atocom.blogspot.com/2011/05/reading-roombarbarella- 11.html (last access 12.12.2019).

[8] All translations from German originate from the author (BME).

[9] The identical twins were named after different species of bloodsucking flies.

[10] Another example occurred in Episode 1 (Forest 1964, 1pp.) and featured Barbarella embracing Ahan (ibid., 7). The third example differs from these as it does not lead to textinternal intimacy. It shows Barbarella being showered by the inhabitants of the realms of the Medusa (Forest 1964, 14) – a procedure to protect her skin, the reader learns on the next page. It is also applied to the male members of the crew, which is not depicted in the panels. Though the disrobing is forced on her, Barbarella is not threatened by it; quite the contrary, she knows about her appeal to extraterrestrials and has a curious, bordering on scientific, interest in finding out about its impact in these new circumstances.

[11] For legal reasons, the text does not include any film stills. All of Barbarella’s costumes can be found at https://www.vintag.es/2018/08/barbarella-costumes.html (last access 12.12.2019).

Literaturverzeichnis

Adler, Renata (1968). Screen: Science + Sex = ‘Barbarella’: Jane Fonda Is Starred in Roger Vadim Film Violence and Gadgetry Set Tone of Movie. The New York Times, 12. October 1968. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019, retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/1968/10/12/archives/screen-science-sex-barbarellajane- fonda-is-starred-in-roger-vadim.html.

Barthes, Roland (1976). The Pleasure of the Text (transl. by R. Miller.). London: Jonathan Cape.

Bates, Dan (1969). Short Notices. Film Quarterly, 22 (3), 58.

Brownie, Barbara, Graydon, Danny (2015). The Superhero Costume. Identity and Disguise in Fact and Fiction. London: Bloomsbury 2015.

Brownie, Barbara (2017). Acts of Undressing. Politics, Eroticism, and Discarded Clothing. London: Bloomsbury.

Buzzi, Stella (1997). Undressing Cinema. Clothing and Identity in the Movies. London: Routledge 1997.

Conrad, Dean (2018). Space Sirens, Scientists and Princesses: The Portrayal of Women in Science Fiction Cinema. Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

Curti, Roberto (2016). Diabolika: Supercriminals, Superheroes and the Comic Book Universe in Italian Cinema. Baltimore, MD: Midnight Marquee Press.

Fabris, Angela, Jörg Helbig (Eds.) (2016). Science-Fiction Kultfilme. Marburg: Schüren.

Finet, Nicolas (2012). Barbarella. In Paul Gravett (Ed.), 1001 Comics die Sie lesen sollten, bevor das Leben vorbei ist (pp. 238f.). Zürich: Edition Olms.

Fletcher, Alicia (2018). Long live Barbarella, Queen of the Galaxy. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019. Retrieved from: https://hollywoodsuite.ca/connect/barbarella/.

Gravett, Paul (2014). Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella: A Landmark in Adult French Comics. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019. Retrieved from: http://www.paulgravett.com/articles/article/ jean_claude_forests_Barbarella.

Grove, Laurence (2010). Comics in French: The European Bande Dessinée in Context. New York: Berghahn Books.

Hall, Justin, (2017). Erotic Comics. In Frank Bramlett, Roy T. Cook & Aaron Meskin (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Comics (pp. 154–63). New York: Routledge.

Haraway, Donna (1985). A Cyborg Manifesto. Accessed 12 Dec. 2019. Retrieved from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/warw/detail.action?docID=4392065.

Havas, Harald, Habarta, Gerhard (Hg.) (1992). Comic Welten. Eine Ausstellung über die Kunst des Bilderlesens. Wien: Edition Comic Forum.

Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1816/2017). Der Sandmann (engl. The Sandman). Stuttgart: Reclam.

Hoffmann, E. T. A. (1816/2006). Nußknacker und Mäusekönig (engl. The Nutcracker and the Mouse King). Stuttgart: Reclam.

Knigge, Andreas (1996). Vom Massenblatt ins multimediale Abenteuer. Frankfurt: Rowohlt.

Knigge, Andreas (2004). 50 Klassiker Comics. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg.

Knigge, Andreas (2016). Geschichte und kulturspezifische Entwicklung des Comics. In Julia Abel, Christian Klein (Ed.), Comics und Graphic Novels. Eine Einführung (pp. 3–37). Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler.

Knigge, Andreas (2017). Sex, Drugs & Rock’n’Roll. In Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland GmbH (Ed.), Comics! Mangas! Graphic Novels! (Bd. 5: Underground & Independent, pp. 6–16). Bonn: Kunsthalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Lathers, Marie (2012). Space Oddities: Women and Outer Space in Popular Film and Culture, 1960–2000. New York: Continuum.

Laverty, Christopher (2016). Fashion in Film. London: Laurence King.

Lembcke, Jerry (2019). Hanoi Jane: War, Sex, & Fantasies of Betrayal. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Leutner, Petra (2015). Die Sprache der Mode am Beispiel von Verbergen und Entblößen. In Rainer Wenrich (Ed.), Die Medialität der Mode. Kleidung als kulturelle Praxis. Perspektiven für eine Modewissenschaft (pp. 315–29). Bielefeld: transcript.

Lötscher, Christine (2018). Unerhörte Philosophien. Utopie, Feminismus und Erotik in Roger Vadims Barbarella. In Hermann Kappelhoff, Christine Lötscher, Daniel Ilger (Ed.), Filmische Seitenblicke. Cinepoetische Exkursionen ins Kino von 1968 (pp. 303–16). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Lofficer, Jean-Marc & Randy (1985). Cruising the Galaxy with Barbarella. An Exotic Voyage inside the International Comic Strip Success of an Erotic Adventuress, the Sexiest Woman in Outer Space. Starlog Magazine, (92), 38.

Lundén, Elizabeth Castaldo (2016). Barbarella’s wardrobe: Exploring Jacques Fonteray’s intergalactic runway. Film, Fashion & Consumption 5, (2), 185–211.

Malcolm, Derek (1968). Fast and Spurious. The Guardian, 16 October 1968, 8.

Mazur, Dan, Danner, Alexander (2014). Comics: A Global History, 1968 to the Present. London: Thames & Hudson.

Power, Aidan (2017). Modern inclinations. Locating European Science Fiction Films of the 1960s and 1970s. In Rainer Rother, Annika Schaefer (Eds.), Future Imperfect. Science Fiction Film (pp. 83–95). Berlin: Bertz+Fischer.

Parks, Lisa (1999). Bringing Barbarella down to Earth. The Astronaut and Feminine Sexuality in the 1960s. In Hilary Radner, Moya Lucket (Eds.), Swinging Single: Representing Sexuality in the 1960s (pp. 253–75). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Schröder, Horst (1982). Bildwelten und Weltenbilder. Science-Fiction Comics in den USA, in Deutschland, England und Frankreich. Hamburg: Carlsen.

Ward, Susan (2017). Textiles. In Alexander Palmer (Ed.), A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Modern Age (pp. 21–42). London: Bloomsburg.

Comics and films

Forrest, Jean-Claude (1964). Barbarella. Paris: Le Terrain Vague.

Mahlich, Hans (Producer), Edward Zajicek (Producer), Maetzig, Kurt (Director) (1960). Der schweigende Stern (engl., First Spaceship on Venus) Kurt Maetzig, East Germany/Poland: DEFA.

Ponti, Carlo (Producer), Petri, Elio (Director) (1965). La Decima Vittima (engl., The 10th Victim). Italy/France: Anchor Bay Entertainment.

De Laurentiis, Dino (Producer), Vadim, Roger (1968). Barbarella. France/Italy: Universal Pictures.

About the Author / Über die Autorin

Barbara Margarethe EggertDr. phil., joined the Department of Art Education at the University of Art and Design Linz in February 2019. She holds an MA both in German Language and Literature / History of Art (University of Hamburg) and in Adult Education / Museum Studies (Humboldt-University Berlin). After finishing her PhD in Art History, Eggert worked as a researcher for Vitra Design Museum (Germany) for two years. Her main research interests are media that combine text and images (special focus: graphic literature and narrative textiles) and exhibitions.

Correspondence address / Korrespondenz-Adresse

barbara-margarethe.eggert@ufg.at